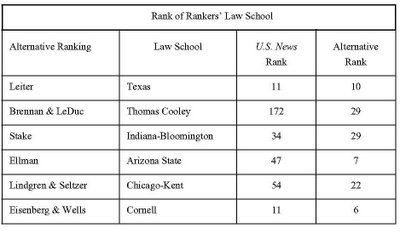

I've been writing and blogging about the USNWR rankings (see

Ratings, Not Rankings and

Eating Our Cake and Having It, Too) and about how people tend to confuse the ranking of a school with the qualifications of individuals at that school. That confusion muddies the waters for potential students, for faculty candidates, and even for dean candidates. Several of my friends are currently involved in dean searches--either on the committee end or the candidate end--and I thought I'd weigh in on some issues for the search committees to consider. So, for what it's worth, here's my advice:

1. No dean's skills can fit every school's most pressing needs. The search committee, the law school, and the university need to think HARD about the most important

next priorities for the school, because different candidates have different strengths, and different schools have different priorities. Does the school have some internal rifts (with faculty, with the central administration) that need to be addressed? Does it need to reach out to external communities? Does it need a large infusion of funds? Does it need encouragement to rethink its curriculum or to increase its scholarly productivity? Does it need to make a "splash" to become better known?

Schools grow in stages, and no dean can come in and "fix" everything all at once. In fact, deans can't "fix" anything by themselves. The whole community needs to pitch in. (That's part of the point of the

Indiana Law Journal piece mentioned above.) Try to figure out the school's likely next move (its most pressing need), and look for dean candidates with a skill set that will match that need.

2. Deans can have "vision" (and should), but the faculty is key to any execution of that vision. Try not to force the candidate to come up with a definitive vision for the school before the candidate has a chance to get to know that school. (Certainly, the "airport interview" stage is too soon.) Candidates can have tentative thoughts about the vision for a school while they're interviewing; but the dean that you're hiring needs to get to know the school before he or she can possibly form a sharper vision about the school and its direction. By the way, please don't put internal candidates at an interviewing disadvantage. Don't ask them questions that you're not asking external candidates--such as their vision for the school--until you reach the stage at which you're asking the external candidates that question. If they volunteer their vision at an earlier stage, of course, listen hard. That's one of the advantages of being an internal candidate: you

do know the school well.

3. Unless your school absolutely, positively needs to hire a "name" to make a splash, take some risks. The skill set that every dean should have will include the ability to balance the wishes of multiple constituencies, to be comfortable relating to a wide variety of people in large group settings and one-on-one, to be skilled at fundraising, to lead AND to manage (those are

different skills, and few deans will be equally skilled at both, but a dean does need to be able to do both), to understand budgets, and to lead by example in terms of a work ethic. It's certainly a big plus if the dean is a skilled teacher and a respected scholar--especially because a smart dean candidate will bargain for tenure as part of the contract. But committees and faculties that focus more on the dean's "faculty" attributes than on the dean's "deaning" talents will be missing some very good candidates. Yes, the dean must blend with the faculty in terms of his or her teaching and research talents, but deaning is

managerial by nature. Deaning involves a learned set of skills--skills that many wonderful professors don't have and aren't that interested in pursuing.

Paul Caron and I have had a really nice dialogue about whether deans should continue to teach and write while they're busy being the dean. It sure helps to have a dean who's not afraid of stepping down and who doesn't

need to stay dean from a fear that he or she can't do anything else. There are some times when a dean

must step down. Take a look at Kent Syverud's new article in the most recent

Journal of Legal Education: How Deans (and Presidents) Should Quit. It's just superb.

Back to the point. TAKE SOME RISKS. Don't look only at sitting or former deans. Take a look at associate deans, clinic directors, legal writing directors, and heads of academic programs and centers--these folks have track records in many of the same job requirements. Take a look at professors who ran businesses in their "prior" lives. Don't spend so much time caring about the candidate's rankings (e.g., where the dean candidate currently works, where the candidate went to undergrad or law school). This is one time that you need to pay more attention to the individual than to any proxy variables for predicting quality. Rankings only address the proxy variables.

Some schools have been very, very successful at hiring a dean who worked

outside the academy because of specific needs those schools have. BE CREATIVE, especially in reaching out to the initial pool of candidates. (And it should go without saying, but I'll say it anyway: professors of color and women have had extra demands on their free time through their years in the academy--typically, too many committee assignments compared to their colleagues, significantly higher mentoring of students and, often, more speaking engagements--so read their CVs with a deeper understanding of the many unwritten demands on their time.)

Broaden your search pool by asking deans at schools you admire for their suggestions. Some schools do very well by hiring consultants or search firms; other schools don't. Ask your colleagues to nominate candidates. REACH OUT.

4. Ask useful questions and get useful references. The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior. Ask each candidate for specific examples of past behavior as that behavior relates to the person's vision, planning, budgeting, fundraising, constituent-balancing, etc. experiences. ASK HARD QUESTIONS. Don't be afraid to give hypotheticals to the candidate. Ask the candidate about what he or she learned from prior failures. (Failures are much better teachers than successes, but you knew that already.) Without outing a candidate (ESPECIALLY a sitting dean candidate), find out when you can ask people who aren't listed as references about the candidate. But beware of (a)

mobbing behavior and (b) anonymous blogs. Then be as specific with the "cold-call" references as you were with the candidate. Follow up the reference's comments with requests for specific examples that back up those comments. And everyone in the process--dean candidates, search committees, law school community members, provosts--need to ask the traditional question that lawyers ask their witnesses as they're preparing them for testimony: "What should I have asked you that I haven't asked already?"

5. Remember that everyone has baggage. Sitting deans have made enemies. So have associate deans and program heads. Internal candidates have special problems with baggage, because everyone's viewing those candidates through the lens of how they "grew up" in that particular law school community. Take a look at

How We Talk Can Change the Way We Work: Seven Languages for Transformation, by Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey. That book has good advice for changing the way you think about your colleagues. Bottom line here: cut your internal and external candidates some slack.

People who make decisions will have enemies, and you don't want a dean who can't make decisions.

6. Dean candidates are human. They need rest breaks, food breaks, and restroom breaks. Sometimes, the two- and three-day interview schedules don't allow for those breaks. I used to call this the dean-interview diet: schools show you food but don't give you time to eat any of it. A good reason for these tight schedules is to mimic the dean's schedule in real life. Just don't get carried away.

7. Pay attention to your HR and affirmative action training. As much as you can, keep the experiences the same for all candidates, and don't ask the illegal questions. Your candidates are learning as much about you as you are about them, and they'll take their impressions of you with them whether or not they get the nod for the job.

8. Pay attention to what the candidates aren't saying as much as what they are saying. I really like Malcolm Gladwell's book

Blink. Get a feel for your initial reaction to each candidate. You're probably picking up some unspoken, unconscious information that the candidate is projecting, including how much the candidate believes in what he or she is saying during the interview. But don't take this advice too far, especially when you're interviewing non-traditional candidates--and, yes,

particularly when you're interviewing candidates of color, women, and GLBT candidates. Any discomfort that you might be feeling might just be a reflection of your lack of familiarity with people in one or more of those groups and not a signal that the candidate is a poor fit for your school.

9. If you want your school to change, you have to be willing to do things differently. I've visited with chairs of dean search committees who have asked me for recommendations for candidates and who want their schools to change in some significant way with the new dean. If the school isn't willing to change the way it (insert

your school's pressing need here) rewards research, interacts with the legal community, balances teaching loads, creates new programs, etc., then what it

really wants is 180 degrees different from what it says it wants. Unless the school is willing to do things differently, it really wants just to stay the same, and it wants to be able to blame the incoming dean for the fact that it

will stay the same.

Many law schools, though, really

don't need to change; they just need to tweak some things. If you don't want your school to change dramatically, tell your candidates that. There are some wonderful candidates whose strengths include changing only at the margins, not at the core. There are also some wonderful candidates who are only interested in serving at schools that want to make big changes. Get the right dean for your school.

10. Remember that the dean's role is a service role.

10. Remember that the dean's role is a service role. Beware the candidate who doesn't love (and I mean LOVE) helping other people achieve

their goals. That's the bottom-line job of a dean. Great deans give their communities support in all sorts of invisible ways. They sacrifice a great deal of their own careers in the process. (See my draft of

Not Quite 'Them', Not Quite 'Us'. I'd still love your comments on this draft, which I'm in the process of revising.) Mind you, every dean candidate has to have a healthy ego, because he or she has to be able to get up, make decisions, and deal with the consequences of those decisions. Only someone with a healthy ego will have the confidence to

risk making decisions, day after day. But if you get even a whiff in the interview that the candidate's ego is out of control, or that he or she wants to be the dean because it's "glamorous" or profitable, that's a huge red flag. Being a dean has its perks, and some of those perks are due to the types of things that deans get to do. (Jeff and I got to fly in NASA's actual shuttle simulator, and I got to throw out the first pitch at a Nebraska baseball game. Yes, I threw overhand.) Some of those perks involve salary, housing, parking spaces, superb support staff, etc. But trust me, being a dean is

at the very least a 6-day-a-week job. Deans are on-call all the time. Being a dean is supremely hard work. You want your dean to be the dean

because she believes that she can help the school achieve some of its goals. (Not to beat a dead horse, but that's why you want a dean whose talents

fit the school's needs.)

I'm also happy to give free advice to dean candidates. (To get a feel for my background as a dean, see, e.g.,

Going from 'Us' to 'Them' in Sixty Seconds,

Of Cat-Herders, Conductors, Tour Guides, and Fearless Leaders,

'Venn' and the Art of Shared Governance, and

Decanal Haiku.)

Deaning is hard work, but it's also one of the most exhilarating jobs I've ever had. I was able to use my "lawyer" brain to solve problems in my favorite environment--the university setting. Even though I don't ever plan to become a dean again, I really did love the (overall) experience at each of the schools that I was privileged to serve. But because I don't want to be a dean again, I'm happy to be a "safe person" for candidates to contact. (And if you're the right person to succeed Dick Morgan as dean of UNLV when he retires next summer,

apply!) Just remember: free advice is worth what you pay for it....

Wishing the schools and the candidates the best,

N.

Larry Kramer thinks that the first year of law school "works." Doug Berman is skeptical. He fears, with reason, that the "tightly scripted" 1L curriculum "works well only for the rare souls (i.e., most folks who become law professors) who really enjoy figuring out the puzzles of the common law and the legal histories behind modern legal realities." As between the Kramer hypothesis and Doug Berman's alternative, I'll side with Doug. Law professors should never, ever forget that the vast majority of their students lead post-graduation lives that bear almost no resemblance to the secular priesthood that is academia. This is true even at Yale.

Larry Kramer thinks that the first year of law school "works." Doug Berman is skeptical. He fears, with reason, that the "tightly scripted" 1L curriculum "works well only for the rare souls (i.e., most folks who become law professors) who really enjoy figuring out the puzzles of the common law and the legal histories behind modern legal realities." As between the Kramer hypothesis and Doug Berman's alternative, I'll side with Doug. Law professors should never, ever forget that the vast majority of their students lead post-graduation lives that bear almost no resemblance to the secular priesthood that is academia. This is true even at Yale. Inspired in part by Douglas Litowitz's cautionary tale, The Destruction of Young Lawyers, I'd like to offer a hypothesis that is as sobering as it is simple. Suppose that the 1L curriculum did absolutely nothing right. That is an extreme assumption, but extreme assumptions can help us sharpen our focus. This utterly inept first-year curriculum may nevertheless succeed in engaging law students' attention because . . . well, they're paying attention as 1Ls. Given the fatuousness of this horrifyingly bad curriculum, students then play out the string just to survive the second and third years of law school. Dead cats, so they say, seem to rebound after market crashes. The apparent success of the first-year law school curriculum may be comparably illusory. It wins by default because 1Ls -- unlike their 2L and 3L counterparts -- haven't had their spirits crushed.

Inspired in part by Douglas Litowitz's cautionary tale, The Destruction of Young Lawyers, I'd like to offer a hypothesis that is as sobering as it is simple. Suppose that the 1L curriculum did absolutely nothing right. That is an extreme assumption, but extreme assumptions can help us sharpen our focus. This utterly inept first-year curriculum may nevertheless succeed in engaging law students' attention because . . . well, they're paying attention as 1Ls. Given the fatuousness of this horrifyingly bad curriculum, students then play out the string just to survive the second and third years of law school. Dead cats, so they say, seem to rebound after market crashes. The apparent success of the first-year law school curriculum may be comparably illusory. It wins by default because 1Ls -- unlike their 2L and 3L counterparts -- haven't had their spirits crushed.

I've been writing and blogging about the USNWR rankings (see

I've been writing and blogging about the USNWR rankings (see  Paul Caron and I have had a really nice dialogue about whether deans should continue to teach and write while they're busy being the dean. It sure helps to have a dean who's not afraid of stepping down and who doesn't need to stay dean from a fear that he or she can't do anything else. There are some times when a dean must step down. Take a look at Kent Syverud's new article in the most recent Journal of Legal Education: How Deans (and Presidents) Should Quit. It's just superb.

Paul Caron and I have had a really nice dialogue about whether deans should continue to teach and write while they're busy being the dean. It sure helps to have a dean who's not afraid of stepping down and who doesn't need to stay dean from a fear that he or she can't do anything else. There are some times when a dean must step down. Take a look at Kent Syverud's new article in the most recent Journal of Legal Education: How Deans (and Presidents) Should Quit. It's just superb. 10. Remember that the dean's role is a service role. Beware the candidate who doesn't love (and I mean LOVE) helping other people achieve their goals. That's the bottom-line job of a dean. Great deans give their communities support in all sorts of invisible ways. They sacrifice a great deal of their own careers in the process. (See my draft of

10. Remember that the dean's role is a service role. Beware the candidate who doesn't love (and I mean LOVE) helping other people achieve their goals. That's the bottom-line job of a dean. Great deans give their communities support in all sorts of invisible ways. They sacrifice a great deal of their own careers in the process. (See my draft of

It's also dean-search season (although I don't think that there's ever an off-season for dean searches). Mobbing behavior can certainly apply to administrators, and now dean candidates also have to worry about stealth mobbing attacks on the Web. Another important Chronicle article,

It's also dean-search season (although I don't think that there's ever an off-season for dean searches). Mobbing behavior can certainly apply to administrators, and now dean candidates also have to worry about stealth mobbing attacks on the Web. Another important Chronicle article,

MoneyLaw warmly welcomes

MoneyLaw warmly welcomes

Much time and effort could be saved, and the same worthwhile goals accomplished, by moving Introduction to Federal Taxation, as many of us teach it, into the first year. What's in the package? Constitutional law analysis? Yes. Administrative law principles? Yes. Statutory and regulatory analysis? Yes. Application of law to facts? Yes. Problem solving? Yes. Planning to avoid problems? Yes. Discussion of ethical considerations? Yes. Awareness of client needs? Yes. Development of interviewing and counselling techniques? Yes. Attention to international issues? Yes. Incorporation of business, social, economic, and political facets of the topics? Yes.

Much time and effort could be saved, and the same worthwhile goals accomplished, by moving Introduction to Federal Taxation, as many of us teach it, into the first year. What's in the package? Constitutional law analysis? Yes. Administrative law principles? Yes. Statutory and regulatory analysis? Yes. Application of law to facts? Yes. Problem solving? Yes. Planning to avoid problems? Yes. Discussion of ethical considerations? Yes. Awareness of client needs? Yes. Development of interviewing and counselling techniques? Yes. Attention to international issues? Yes. Incorporation of business, social, economic, and political facets of the topics? Yes.

Now it's time to talk about

Now it's time to talk about  The rest, of course, is baseball history. Boras is the most powerful agent in baseball, perhaps in all of professional sports. His clients routinely command more than they are expected to receive. His masterful negotiation of a $252 million contract (yes, a quarter of a billion dollars) for Alex Rodriguez ruined the Texas Rangers and now taunts the New York Yankees. When they call you the "

The rest, of course, is baseball history. Boras is the most powerful agent in baseball, perhaps in all of professional sports. His clients routinely command more than they are expected to receive. His masterful negotiation of a $252 million contract (yes, a quarter of a billion dollars) for Alex Rodriguez ruined the Texas Rangers and now taunts the New York Yankees. When they call you the "

Why do law school courses bear so little resemblance to the real-world conditions in which most law school graduates eventually work? My MoneyLaw colleague Jeff Harrison, with good reason, would regard this as further evidence of

Why do law school courses bear so little resemblance to the real-world conditions in which most law school graduates eventually work? My MoneyLaw colleague Jeff Harrison, with good reason, would regard this as further evidence of  To be sure, Harvard with much fanfare has announced

To be sure, Harvard with much fanfare has announced  Much hinges on Harvard's third course, the problem-solving course that will also "introduc[e] students to theoretical frameworks illuminating legal doctrines and institutions." This course seems most likely of the three new offerings to present "fact-intensive problems as they arise in the world (rather than digested into legal doctrines in appellate opinions) and to generate and evaluate solutions through private ordering, regulation, litigation and other strategies."

Much hinges on Harvard's third course, the problem-solving course that will also "introduc[e] students to theoretical frameworks illuminating legal doctrines and institutions." This course seems most likely of the three new offerings to present "fact-intensive problems as they arise in the world (rather than digested into legal doctrines in appellate opinions) and to generate and evaluate solutions through private ordering, regulation, litigation and other strategies."