INSTANT GRAVITAS.

No, I’m not trying to win the “worst co-blogger” award here at the Jurisdynamics Network, or be the Anti-Jurisdynamic Idol. I wish I could explain the extreme paucity (as in, nothing for over a month) of blogging either at my blog or MoneyLaw with “I’ve been busy.” But given the audience of lawyers, professors, and aspiring lawyers and professors, who isn’t busy? And it just gets busier.

I guess what I mean to say is, I’ve been busy, and I’m new at all this and so it’s easier to be overwhelmed. Blogging, and heck, eating and sleeping have been pushed to the side. It's to the point where I get pleas to call, to blog, and to come home for Thanksgiving. Is this something one should admit, particularly if one is an Aspiring Law Prof? Shouldn’t I, as a MoneyLawyer, be so good at the game, so good at gaming the system, and so much a heavy hitter and major league player (enough baseball metaphors for the Moneyballers out there?) that it should all be “easy” for me?

Not if you’re new to the game. So let me be, as I am often called, “characteristically frank.” I am the neophyte, the newbie, the rookie, the greenhorn, the new kid on the block. There is always a learning curve to any profession, and I’m at the first tail of the curve, so much at the beginning that the apex of the parabola isn’t even in sight. When you’re new at things, it’s easy to just think you should give up this juggling hobby for a while when you have too many balls in the air.

So what have I been busy with? Trying to learn how to work like, act like, and be like a law professor when I’m still basically a student in a “glorified JD program.” I have been working on my my heavily doctrinal LLM thesis for my Preeminent Federalism Scholar advisor. I have been writing a second, more "cutting edge" article using a sociological approach to the employment discrimination law. I don't think I am admitting something shameful when I say that writing two articles in the same 4 month period is quite difficult. In addition to all that, I have been doing course work for my LLM degree, and am beginning preparations for finals, which I am growing to resent (the grumble that an LLM is a glorified JD for American-trained laywers has some traction). I have been, against all expectation (if you take the standard past habit --> future behavior approach) having a life outside of law school. And it's all taken a toll on this blogging thing (and eating/sleeping thing).

Recently, and I won't say when or where or about what, I attended my first law professor conference. No, I'm not a law professor yet. So it was painfully obvious to others exactly my status since it was listed on the program and I was quite upfront about it--no sense pretending that you belong when you've crashed the party. Pretty much, every time I introduced myself I had to say: "yes, I'm a lawyer; no I'm not a law professor yet; yes, I'm quite young, aren't I; yes, being one of the few American LLMs at Liberal College Law is great!; no, I'm not going on the market yet, but thanks for the encouragement; and yes, attending a law professor conference when you're not a law professor is a bit intimidating, now that you mention it."

Gearing up for the conference, I was freaking out. I freaked out about my article and it's "work in progress" state; I freaked out about my Power Point presentation and whether the slides coherently communicted my paper; and I freaked out about being discovered as a total fraud and poseur who really, really should have gone to English literature grad school. So in addition to working without sleep or food for a month, I assembled an Instant Gravitas Kit: Power Suit, Power Heels, Power Point, and the final touch, glasses for extra gravitas. I think they make me look a bit older. When you are under 30 years old and are a petite 5'2" woman with a deplorably "cute" aura, you actually want to look a little older. And I do work in employment discrimination, so I don't take it for granted that I will be taken seriously. Having a stress-related sore throat lowered and deepened my voice a tiny bit, so even if my voice wasn't stentorian it was at least less like an evil possessed child from a Stephen King movie. If my paper turned out to be a complete failure and my presentation a complete joke, then at least I would have the appearance of gravitas. I would be like Stephen Colbert: all sound and fury, signifying nothing, but at least capable of winning a gravitas-off with the grave, stentorian, soundly named Stone Phillips. Glasses = Instant Gravitas.

Turns out, the freakouts were all for naught. The conference went very smoothly--I made lots of contacts, and impressed my fellow attendees with my comments and breadth and depth of legal knowledge, and most importantly my moxie for inviting myself to the conference in the first place (I am a MoneyLawyer). So while I was sort of the neophyte novelty at the conference, I was at least obviously serious about becoming an academic. And despite the fact that my USB key broke right as I was uploading my slides, my presentation went well (and ironically, real emergencies don't make you freak out, they just make you act very quickly). I made a few self-effacing remarks in acknowledgement of my status and chutzpah, made a joke that went over well, and had some slide effects that looked pretty cool. But more importantly, my paper went over very well--with scholars who write in the same area and who know far more than I do about the entire field. I was able to answer all the questions, and nothing surprised me--to my surprise. I was prepared, I had a sound paper idea, and my presentation went great. I had people coming up to me offering help with the meat market when I go in a few years, encouraging me to go on the market right now, and telling me that they were excited by and impressed by my work. One mentor prof in particular urged me to go on the market rather than pursue a SJD, reasoning that I could do a lot of the research and packaging and tool-kit building on the job, rather than through an advanced law degree. "Learn by doing," is what he seemed to be saying.

And so I am wondering. Why don't I feel ready? (Other than the fact that I'm not, at least not without at least 3 publications under my belt). Why is it that despite the success of my first "learn by doing" experience, I feel like I don't know what I'm doing? I fully admit that it is hard for a newbie aspiring academic to feel comfortable, at least in the beginning. Even if it's work you love and want to do for the rest of your life, it's feels hard doing it when you are just starting to assemble the skills and assurance necessary to make it go easier. It's not that I doubt that I can do it, I just wish doing it went more efficiently, quickly, and smoothly. It seems so hard when you're beginning: to come up with that novel, useful, interesting argument; to research it well and write about it cogently; to present it clearly; to feel like you have the requisite seriousness and do not need to affect gravitas. Even if it works out in the end, the process feels so riddled with doubt and difficulty. What neophytes lack most is probably confidence, which is why rookie MoneyLawyers feel like they are out of their league--they are with the Majors, and just a few months ago they were playing for the Minors.

Maybe I shouldn't feel so insecure. Maybe, as my mentor friends say, it does get easier with practice, and what I'm feeling now isn't a valid sense of incompetence, but just first jitters and natural newbie awkwardness. Even the best players in the Major leagues (if they are good academics) have to keep practicing, keep in shape (by sharpening their tools or expanding their tool kits), and go through Spring Training (say, in March and again in August) year after year. It doesn't get easier in terms of how much work it is or what you have to do to keep being a good academic. But it feels easier to those who do it for long enough and stick with it, and who risk failure for great reward and who take risks in order to stretch and grow. Those who reach have a better chance of obtaining their goal than those who never even extend their hand.

Maybe, maybe it gets easier. I hope so. It seemed so much easier at the conference than preparing for the conference: actually doing it felt easier than learning how to do it. So maybe I should learn by doing, even if I feel like I don't know what I'm doing.

Either way, I'm sticking with glasses, just for that extra little bit of gravitas.

A number of readers assume that my posts are always about my home School here in Gatorland. Yes, much of the time I am inspired by Gatorland events, (and David Lodge) but judging by what people at other schools tell me, their schools have the same basic anti-MoneyLaw tendencies. Based on statistics I have seen, one way my School clearly is not different is in the lack of interest in hiring to promote ideological diversity. The resulting lack diversity is hard on old fashion lefties like me and the smattering of conservatives who are on a faculty. (Here, I think, we have 1 conservative and no libertarians, but maybe some are in hiding.) Who are we supposed to argue with and how do we test our ideas? It makes for a very uninspiring environment. Writing for and talking to the choir is as boring as talking to a rabid pro-lifer about what constitutes a person – there is only one acceptable answer. I do not understand why this is tolerable to so many. The thrill of intellectual adventure seems lost.

A number of readers assume that my posts are always about my home School here in Gatorland. Yes, much of the time I am inspired by Gatorland events, (and David Lodge) but judging by what people at other schools tell me, their schools have the same basic anti-MoneyLaw tendencies. Based on statistics I have seen, one way my School clearly is not different is in the lack of interest in hiring to promote ideological diversity. The resulting lack diversity is hard on old fashion lefties like me and the smattering of conservatives who are on a faculty. (Here, I think, we have 1 conservative and no libertarians, but maybe some are in hiding.) Who are we supposed to argue with and how do we test our ideas? It makes for a very uninspiring environment. Writing for and talking to the choir is as boring as talking to a rabid pro-lifer about what constitutes a person – there is only one acceptable answer. I do not understand why this is tolerable to so many. The thrill of intellectual adventure seems lost.

(On this read Julian Barnes’ The History of the World in Ten and a Half Chapters, where we learn what many of us had expected all along: that there were two Arks and one was lost in the flood and, for the most part, no one has given it a second thought.)

(On this read Julian Barnes’ The History of the World in Ten and a Half Chapters, where we learn what many of us had expected all along: that there were two Arks and one was lost in the flood and, for the most part, no one has given it a second thought.)

Miss Gray's personal heroes included

Miss Gray's personal heroes included

It would be that you're all okay

It would be that you're all okay As much as I admire N.J.L.S., whose

As much as I admire N.J.L.S., whose

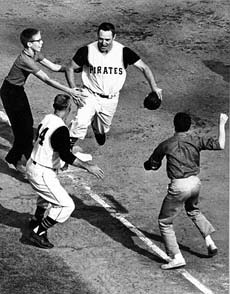

MoneyLaw is pleased to confer a Mazeroski Medal of Merit on

MoneyLaw is pleased to confer a Mazeroski Medal of Merit on

The prize fight between Jeff Harrison and Orin Kerr in the commentary on

The prize fight between Jeff Harrison and Orin Kerr in the commentary on  Think this one through for just one minute. It is yet another instance of the

Think this one through for just one minute. It is yet another instance of the

So, Orin, we have traveled a long way in pursuit of some clarity. Let's see if we can find it. The presence of a VAP post on a teaching candidate's CV may explain how she or he found the time to write. But we should not be so bedazzled by the prestige of the school at which the candidate held the post that we neglect to read and evaluate the actual portfolio. And perhaps even more important, it behooves us not to treat a VAP stint as this generation's obligatory rite of academic passage, in the sense that law review membership and a clerkship have historically represented compulsory stops on the road to becoming a law professor.

So, Orin, we have traveled a long way in pursuit of some clarity. Let's see if we can find it. The presence of a VAP post on a teaching candidate's CV may explain how she or he found the time to write. But we should not be so bedazzled by the prestige of the school at which the candidate held the post that we neglect to read and evaluate the actual portfolio. And perhaps even more important, it behooves us not to treat a VAP stint as this generation's obligatory rite of academic passage, in the sense that law review membership and a clerkship have historically represented compulsory stops on the road to becoming a law professor.

Do the math. Phenoms aside, Americans begin college no earlier than 18. And then there's college itself. Remember the scene in

Do the math. Phenoms aside, Americans begin college no earlier than 18. And then there's college itself. Remember the scene in

Although Paul, Ronen, Al, and I will undoubtly revisit this issue in greater depth in future posts, the release of the Doyle database's new numbers provides an apt occasion for pondering precisely why law review citation statistics matter to MoneyLaw and the search for ways to win this unfair academic game. Baseball, not surprisingly, provides a basis for comparison and perhaps even the inspiration for a new set of measurements of academic merit.

Although Paul, Ronen, Al, and I will undoubtly revisit this issue in greater depth in future posts, the release of the Doyle database's new numbers provides an apt occasion for pondering precisely why law review citation statistics matter to MoneyLaw and the search for ways to win this unfair academic game. Baseball, not surprisingly, provides a basis for comparison and perhaps even the inspiration for a new set of measurements of academic merit. Baseball not only fails to measure errors properly; it has no official way of filtering out superlative pitching from mediocre fielding.

Baseball not only fails to measure errors properly; it has no official way of filtering out superlative pitching from mediocre fielding.

Of all the technological innovations that have transformed law schools in the Internet age, none may be more useful than the wireless network. Knowing that broadband access is available anywhere, any time in a law school is a great source of comfort. The content itself isn't bad, either.

Of all the technological innovations that have transformed law schools in the Internet age, none may be more useful than the wireless network. Knowing that broadband access is available anywhere, any time in a law school is a great source of comfort. The content itself isn't bad, either. Yes, wireless networks facilitate Internet access. That means sports and gossip pages, personal e-mail, perhaps even online poker during class. All that is distracting, arguably in a way that crossword puzzles are not, since other students can see the offending screens. But a ban on wireless access simply restores the primacy of solitaire, hearts, Freecell, and Minesweeper.

Yes, wireless networks facilitate Internet access. That means sports and gossip pages, personal e-mail, perhaps even online poker during class. All that is distracting, arguably in a way that crossword puzzles are not, since other students can see the offending screens. But a ban on wireless access simply restores the primacy of solitaire, hearts, Freecell, and Minesweeper.

Big 10 scheduling gave us something this year that the BCS system rarely if ever delivers: a game between teams that are indisputably the best in the country. And it was a very, very good game. If Michigan recovers the onside kick -- admittedly a low-percentage play under any conditions -- momentum carries the Wolverines past the Buckeyes. Give credit to the voters who kept Michigan #2 in the polls. Rarely does #2 keep its position after losing to #1, even though that is the expected outcome, and the team that is promoted to the second spot might have done nothing besides remaining idle. The voters kept Michael Vick's Virginia Tech squad at #2 after they lost a 42-29 thriller to Florida State in the 2000 Sugar Bowl, but that is the exception and not the rule.

Big 10 scheduling gave us something this year that the BCS system rarely if ever delivers: a game between teams that are indisputably the best in the country. And it was a very, very good game. If Michigan recovers the onside kick -- admittedly a low-percentage play under any conditions -- momentum carries the Wolverines past the Buckeyes. Give credit to the voters who kept Michigan #2 in the polls. Rarely does #2 keep its position after losing to #1, even though that is the expected outcome, and the team that is promoted to the second spot might have done nothing besides remaining idle. The voters kept Michael Vick's Virginia Tech squad at #2 after they lost a 42-29 thriller to Florida State in the 2000 Sugar Bowl, but that is the exception and not the rule.