| Another brick in the wall |

Another brick in the wall

Elite trappings

“Over the last 20 years, every president has been a graduate of Yale.” — Elizabeth Bumiller, The snare of privilege  |

The race for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination has been as bizarre as it has been long. The battle between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, perhaps because it has stressed symbol and style over substance, has shed powerful light on one MoneyLaw point: the political and practical impotence of elite educational credentials.

Consider this column by the New York Times' Elizabeth Bumiller:

I am absorbing all of this in a way that Michelle Obama, savvy political spouse that she is, should appreciate. This moment in political history reinforces my lifelong pride in being an American. By pushing Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and John McCain through an elaborate exercise in nonelite bona fides, the American electorate has been expressing three beliefs about elite education that are as deeply true as they are intensely felt:

I am absorbing all of this in a way that Michelle Obama, savvy political spouse that she is, should appreciate. This moment in political history reinforces my lifelong pride in being an American. By pushing Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, and John McCain through an elaborate exercise in nonelite bona fides, the American electorate has been expressing three beliefs about elite education that are as deeply true as they are intensely felt:- Elite education isn't really meritocratic. Expressions of noblesse oblige by the educational elite speak less eloquently than elite institutions' actions and policies. Look at the way they admit students and price tuition: a talented student from a lower-income family has no greater chance of being admitted to an elite college, let alone affording it, than a mediocre student from a wealthier family.

- Elite education teaches its wards some fairly goofy things. World enough and time wouldn't accommodate a full discussion of this topic. Let's just focus on what elite institutions' leaders often forget — not in spite of but rather because of the socially rarified settings in which they have spent their lives: Students go to school in order to better themselves economically, and the schools in turn must be accountable to their students and their graduates in material terms. These are insights that come along as a natural incident of a working-class upbringing, but today's elite institutions neither seek nor yield classes — let alone faculties — that reflect that source of cultural wealth.

- Elite education doesn't do that much for you anyway, relative to less elite and more affordable alternatives. Who needs the Ivy League? Or, for that matter, public schools that have forsaken their land-grant missions in quixotic quests for impressionistic prestige, schools that have abandoned Das Volk in favor of a Drang nach Hochmütigkeit? Having been spared the task of retiring debt incurred to take classes from professors who are overrated almost precisely to the degree that they are overpaid may be the best thing that ever happens to graduates of nonelite institutions.

In the end, as with Lux et Veritas, these are the things that matter: The signaling function of education, elite or otherwise, falls far short of things that the best students learn for themselves and teach each other, no matter where they go to school. Neither elite credentials nor even native talent counts as much as hard work, persistence, and fundamental decency. The candidate who best reflects these values will be getting my vote in November, and with any luck a large number of other voters — at the real ballot box and in the sham poll called the U.S. News & World Report survey — will choose in like fashion.

In the end, as with Lux et Veritas, these are the things that matter: The signaling function of education, elite or otherwise, falls far short of things that the best students learn for themselves and teach each other, no matter where they go to school. Neither elite credentials nor even native talent counts as much as hard work, persistence, and fundamental decency. The candidate who best reflects these values will be getting my vote in November, and with any luck a large number of other voters — at the real ballot box and in the sham poll called the U.S. News & World Report survey — will choose in like fashion.

Traveling Without the Kids

For information about Massachusetts divorce and family law, see the divorce and family law page of my law firm website.

The Alternative to CORI Reform: Let's Just Order Them to Re-Offend

Thanks to John Monahan and the Worcester Telegram and Gazette for an excellent article yesterday about the fact that CORI reform is now unlikely. The CORI reform proposals, introduced and backed by Governor Patrick, and as discussed and strongly supported by me here at this blog,

have run aground in the House Judiciary Committee, and the chances of the law covering criminal records being reformed before the Legislature ends formal sessions for the year in July now seem remote.The reason? According to the article:

Earlier this week, Rep. Eugene O’Flaherty, D-Boston, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, reported that the bill has run into a lot of “roadblocks” because of the many complicated issues involving reintegration of ex-convicts into communities and the interest of employers to job screen applicants. His comments gave little hope the bill could be acted on soon.

Right. So, in other words, the CORI reform effort, which is in fact the effort to help reintegrate past offenders into society, by giving them a chance to housing and a job, and that is by reducing the extremely overbroad access of employers to information - information about not just convictions, but even about long-ago charges that led to dismissals or acquittals - has been derailed because employers still want that information, and they have the power on Beacon Hill.

This will be great for these employers, as they will continue to be able easily to identify a special kind of underclass, one that they can either avoid hiring altogether or relegate to lower paying, less desirable employment due to its much diminished bargaining power in the labor market.

But the collateral consequences of failure to reform CORI are that taxpayers will have to pay more for social services to make up for the economic deficiencies, and also more for the criminal justice system - including for law enforcement, our overcrowded jails, and the criminal courts and probation departments - as that criminal justice system will continue to be busy, if not busier, as a result.

The big employers blocking change are at the top of the economic ladder. Basically this is just another way in which the most powerful, wealthy interests are asking the majority of us as taxpayers to pay more taxes to cover the collateral damage that inevitably results from a system designed and created more for the benefit of these most powerful, wealthy interests than for anyone else.

I'm not saying individuals are not responsible for their crimes. However, I am a realist, and I believe the evidence is overwhelming that good, sound economic policies reduce crime. The attempt to block CORI reform seems to me to be just another unsound economic policy (and it is assuredly an economic policy as much as it is a criminal policy) and it probably deserves a chapter in the ongoing, unwritten history of Class War.

I have heard fellow criminal defense attorneys complain, often after a judge in a criminal case gives a poor criminal defendant on probation a short period of time to come up with very stiff probation fees, or when a judge sets very onerous conditions on probation, that "the judge just set him up to fail" or even - and this is my personal favorite - that "the judge just ordered him to re-offend."

Sort of a cynical joke among lawyers, maybe, but this is no real joke for those who have been in the world of crime, and now can't get a job or housing because of it. There are certainly criminal defendants on probation who have committed new crimes in order to get the money to pay their probation, court fees, restitution, or other court-related expenses, as they often find it difficult, if not impossible, to find a legitimate job.

And if former criminals, just like those currently on probation, also can't get a legitimate job or housing, they are more likely both to become dependent upon government benefits of one kind or another, and also either to steal, or sell drugs, or commit other crimes, just in order to survive. This is the difficult, cold, hard reality of former criminal offenders.

So I must ask, in that same, lawyerly cynical spirit: Is our legislature, at the behest of employers, going to deny CORI reform and instead "order former criminals to re-offend"?

For information and links related to Massachusetts criminal law see the criminal defense page of my law firm website.

Texas Appellate Court Rules Against Government's Illegal Raid on FLDS

With no thanks to the national ACLU, and other suddenly silent, supposed defenders of civil liberties, the Third Court of Appeals in Texas just did the right thing in denouncing the outrageous government raid on the FLDS sect, and reversing the boneheaded trial court ruling. The appellate court's opinion is here. The appellate court, to its great credit, has echoed the concerns raised by those of us who are truly concerned about civil liberties, no matter whose liberties they are, and who are not afraid to say so publicly.

I have previously denounced the actions of the Texas authorities in unnecessarily and wrongly wreaking havoc upon hundreds of families, and I have joined a few others in criticizing the dishonest way in which the Texas government has done so, in what has become the biggest custody case in this country. But I say again: Shame, shame on the Texas authorities for their damn lies and statistics, their false pretexts, all leading to their illegal raid on an unpopular religious community, and traumatization of hundreds of families. Hopefully the court's ruling will not be too little, too late, for the hundreds of completely innocent individuals, and especially their victimized children, the vast majority of whom can only be proven to have been mistreated by the government that presumes to protect them.

And shame, shame on the media for covering this story in a politically correct fashion, and thereby misleading the public by easily succumbing to the government's obvious media manipulation. For more on this, see my three previous posts on this, Destroying the Polygamist Village to Save It, From Aluminum Tubes to Broken Bones: Texans, Lies and Statistics, and More On The Texas Polygamy Scare and The Civil Liberties Non-Scare, linking to previous stories and blog posts from Grits for Breakfast, and The Volokh Conspiracy, Wendy Kaminer, The Polygamy Files, and the few other voices around the country who have courageously come out in favor of the law, the constitution, civil liberties, and sanity, while they have also simultaneously, and virtually alone, reported accurately on this story to fill in for the most prominent national reporters and commentators who have cowardly gone AWOL. OK, rant over.

ASSOCIATED PRESS:

SAN ANGELO, Texas - In a ruling that could torpedo the case against the West Texas polygamist sect, a state appeals court Thursday said authorities had no right to seize more than 440 children in a raid on the splinter group's ranch last month.

It was unclear how many children were affected by the ruling. The state took 464 children into custody in April, but Thursday's ruling directly applied to the children of 48 sect mothers represented by the Texas Rio Grande Legal Aide, said Cynthia Martinez of the agency. About 200 parents are involved in the polygamy case.

The Third Court of Appeals in Austin ruled that the state offered "legally and factually insufficient" grounds for the "extreme" measure of removing all children from the ranch, from babies to teenagers.

The state never provided evidence that the children were in any immediate danger, the only grounds in Texas law for taking children from their parents without court approval, the appeals court said.

It also failed to show evidence that more than five of the teenage girls were being sexually abused, and never alleged any sexual or physical abuse against the other children, the court said.

It was not immediately clear whether the children scattered across foster facilities statewide might soon be reunited with parents. The ruling gave Texas District Judge Barbara Walther 10 days to vacate her custody order, and the state could appeal.

For information about Massachusetts divorce and family law, see the divorce and family law page of my law firm website.

The instruction of youth and the welfare of the state

|    The University of Minnesota Northrop Auditorium, 1929 |

| Founded in the Faith that Men are Ennobled by Understanding Dedicated to the Advancement of Learning and the Search for Truth Devoted to the Instruction of Youth and the Welfare of the State | |

Let's read that again: Devoted to the Instruction of Youth and the Welfare of the State. So concludes the lofty and inspiring inscription on Northrop Auditorium, the architectural center of gravity on the Twin Cities campus of the University of Minnesota.

Northrop's inscription echoes the Morrill Land-Grant College Act of 1862, Act of July 2, 1862, ch.130, 12 Stat. 503 (codified as amended at 7 U.S.C. § 304), the legislative foundation of a network that now spans more than 100 colleges and universities in the United States and its territories. The original Morrill Act committed each state to establishing

Amendments in 1890 and 1994 extended the land grant system to historically black colleges and universities and to Native American institutions. Collectively, land grant colleges represent access to higher education for an enormous number of working-class and nontraditional students. As I often say of my own school, the University of Louisville (which is not a land grant college but does serve a comparable mission in a metropolitan setting), these are the universities that serve first generations and provide second chances.at least one college where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactics, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes on the several pursuits and professions in life.

One of the keystones of the land grant system is affordability. For decades the cost of higher education has been increasing at a rate far outpacing that of middle class wages. The cost of elite education has risen even more rapidly. As Marie Reilly has explained in this forum, there is strong reason to suspect that universities have plowed the revenues from those tuition hikes into prestige-enhancing measures that deliver little if any value to students who are borrowing heavily for ever-decreasing returns on their educational investments. This is especially true at elite institutions. The contribution of land grant colleges and other public schools to educational access has never been greater, or more important.

All this is prologue to an important post by Bill Gleason, a faculty member in the University of Minnesota's department of laboratory medicine and pathology and the author of The Periodic Table. In Affordability at The University of Minnesota: Priorities for the Short and Long Term, Bill questions his university's commitment to access and affordability — the bedrock of the land grant system — as Minnesota's central administration continues its quixotic pursuit of its stated "aspiration to be one of the top three public research universities in the world." Herewith the remarks Bill made at a May 21, 2008, budget forum sponsored by the University of Minnesota's Board of Regents:

All this is prologue to an important post by Bill Gleason, a faculty member in the University of Minnesota's department of laboratory medicine and pathology and the author of The Periodic Table. In Affordability at The University of Minnesota: Priorities for the Short and Long Term, Bill questions his university's commitment to access and affordability — the bedrock of the land grant system — as Minnesota's central administration continues its quixotic pursuit of its stated "aspiration to be one of the top three public research universities in the world." Herewith the remarks Bill made at a May 21, 2008, budget forum sponsored by the University of Minnesota's Board of Regents:Minnesotans expect us to be fair in providing access to the University for their sons and daughters.

If we do not provide reasonable access — including access for those who are underprepared and historically underrepresented in higher education and in the upper levels of our socioeconomic life, the taxpayers and state government of Minnesota will turn their backs on our graduate, research, and outreach functions.

Simply stated, it is imperative that we continue to embrace our land-grant roots if we are to thrive.

My first point is that currently student debt is crushing and that the highest priority should be put on addressing this problem.

My first point is that currently student debt is crushing and that the highest priority should be put on addressing this problem.The claim that scholarships can offset fees and tuition is an empty one. The focus needs to shift to student debt.

According to Kiplinger, we have the highest average student loan debt of any (public) school in the Big Ten — $25,000.

And this is just an average. Undergraduates working in my lab have debts greater than this — people who were born in Vietnam, Poland, and the Ukraine. To give but one real example: both parents of one of my Vietnamese students work in an Austin meat-packing plant. She should be going to medical school, but informed me recently that she would have to seek employment immediately after graduation in order to pay off her debts.

Our Big Ten-leading student debt is simply unacceptable and taking steps to correct it should be of highest priority.

My second point is the hubris exhibited by our administration's continual parroting of the phrase: "ambitious aspiration to be one of the top three public research universities in the world."

As the faculty senate research committee put it last September:

Is this a time to be talking about getting into the top three? When units cannot maintain their research capacity, how can they get to the top three? There is little to suggest that the University is on an upward trajectory.In response to perceived criticism, President Bruininks has said:

I've heard some of the 'doubters' say things like, I'd settle for best in the Big Ten. Students don't choose the University of Minnesota for (a) mediocre future.We'd be extremely fortunate to be one of the best schools in the Big Ten. Continuing on with this Orwellian third best public research university in the world business, in light of reality, is an embarrassment and only serves to make us look naive and foolish.

To conclude, again with the words of Mark Yudof:

Some would urge the University to pull back on its land-grant responsibilities.

But at what cost? To save so little and destroy so much? Any short-term gain to research or graduate and professional programs occasioned by cutbacks to the core will be self-defeating. The result will be a decreased level of public support for the entire University enterprise. The University is built on its undergraduate program. If the foundation cracks, the whole edifice is in jeopardy.

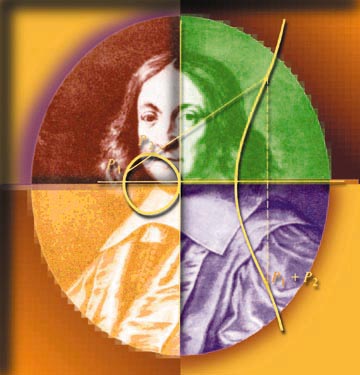

Law's double helix

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” ─ that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. John Keats Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819) |

The concluding couplet in John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn (1819) — “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. — is arguably the most famous pair of lines in Keats's body of work, perhaps in all of English poetry in the Romantic tradition. The suggestion that truth and beauty might be one has proved so seductive that mathematicians and physicists often rely on unproven links between truth, beauty, and symmetry to frame their hypotheses.

Keats may have stated the unity of truth and beauty in memorable literary terms, but mathematics may be the discipline that relies most heavily on it. Often enough, though not invariably, the unity of truth and beauty holds. What is beautiful is true, and what is true in turn is beautiful. Exceptions do arise — the computer-assisted proof of the four-color theorem and Andrew Wiles's proof of Fermat's last theorem are salient examples of mathematical proofs that look more like rambling narratives or even telephone directories than odes.

Keats may have stated the unity of truth and beauty in memorable literary terms, but mathematics may be the discipline that relies most heavily on it. Often enough, though not invariably, the unity of truth and beauty holds. What is beautiful is true, and what is true in turn is beautiful. Exceptions do arise — the computer-assisted proof of the four-color theorem and Andrew Wiles's proof of Fermat's last theorem are salient examples of mathematical proofs that look more like rambling narratives or even telephone directories than odes.Nevertheless, philosophers, poets, and physicists wax rhapsodic in lauding the points in intellectual space where truth achieves what Bertrand Russell called "a beauty cold and austere." Edna St. Vincent Millay echoed this sentiment when she wrote, "Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare." According to the physicist Hermann Weyl, the best scientific work has “always tried to unite the true with the beautiful.” But when he “had to choose one or the other,” Weyl “usually chose the beautiful.”

How firmly does Keats's unity — the unity of truth and beauty — hold in law?

Read the rest of this post . . .True to the serendipitous way in which law itself arises, I stumbled unto what I believe to be the law's best description of Keats's unity in — of all things — a memoir described as a uniquely powerful first-personal account of science in action. In the opening pages of The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (1st ed. 1969; reprint 2001), James D. Watson explained how the quest for beauty and the quirks of human culture both bent the trajectory of the quest for the double helix:

Law proceeds on terms somewhere between the extremes of Euclid's airtight Elements and the comprehensive computer-aided proof of the four-color theorem. As Francis Crick and James Watson discovered when they sought to unlock the structure of DNA, the quest for the social truth that law embodies may begin in "the belief that the truth, once found, would be simple as well as pretty." That gesture of "youthful arrogance," however, rarely if ever yields the truth on its own. No less than their scientific counterparts, lawyers follow an "incomplete and hurried" protocol by which they "frequently decide to like or dislike a new idea or acquaintance."[S]cience seldom proceeds in the straightforward logical manner imagined by outsiders. Instead, its steps forward (and sometimes backward) are often very human events in which personalities and cultural traditions play major roles. To this end I have attempted to re-create my first impressions of the relevant events and personalities rather than present an assessment which takes into account the many facts I have learned since the structure was found. Although the latter approach might be more objective, it would fail to convey the spirit of an adventure characterized both by youthful arrogance and by the belief that the truth, once found, would be simple as well as pretty. Thus many of the comments may seem one-sided and unfair, but this is often the case in the incomplete and hurried way in which human beings frequently decide to like or dislike a new idea or acquaintance.

Like other outsiders, law students often envision the formation, interpretation, and enforcement of law as a straightforward, even logical process. They soon learn, as Oliver Wendell Holmes observed in the opening lines of The Common Law, that "[t]he life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience." Even as Watson acknowledged how science lurched "forward (and sometimes backward)" in response to "very human events in which personalities and cultural traditions play major roles," Holmes recognized that law does not so much observe syllogisms as reflect "[t]he felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow" citizens.

Like other outsiders, law students often envision the formation, interpretation, and enforcement of law as a straightforward, even logical process. They soon learn, as Oliver Wendell Holmes observed in the opening lines of The Common Law, that "[t]he life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience." Even as Watson acknowledged how science lurched "forward (and sometimes backward)" in response to "very human events in which personalities and cultural traditions play major roles," Holmes recognized that law does not so much observe syllogisms as reflect "[t]he felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow" citizens.Two intertwined strands run through all law. One strand represents the cold mathematical logic that the LSAT purports to measure, the austere beauty of legal reason deduced without regard to the social circumstances in which law must be made, enforced, and lived. The other strand speaks in historical, even literary or lyrical terms. That manifestation of truth in law, as Holmes explained, "embodies the story of a nation's development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics." That is all you know in law, and all you need to know.

Innovative Thinking: From the ABA to the "G-Man"

Innovative thinking often comes from unlikely sources. With March Madness behind us and the excitement of the NBA playoffs hitting its peak, it is time to pay tribute to the ABA. The ABA was a freewheeling league that featured big afros, the infamous red-white-and-blue ball, and focused on a flashy, fast style of play. In a purely economic sense, the ABA was a failure. It hemorrhaged cash and was eventually absorbed by the NBA. For most of its existence it could not secure a television deal, so much of what we know about the ABA comes from word-of-mouth sources or online compilations like Remember the ABA. The ABA was beloved by fans (Jim, I'm sure you have heard more than your fill about the Kentucky Colonels). One of my favorites is Artis Gilmore, who stood 7'6'' if you counted the afro:

Underneath the party atmosphere, the ABA was a haven of innovative thinking that revolutionized the game of basketball. The ABA implemented the three-point shot, slam dunk, and the fast pace of the up-tempo modern game. Now the new wave of innovation is hitting basketball — the Moneyball approach. The Houston Rockets have hired Daryl Morey, the NBA's first Moneyball general manager. Aside from being tall, Morey does not look the part. He has not played basketball since high school, and he has never been a coach or scout. What

Underneath the party atmosphere, the ABA was a haven of innovative thinking that revolutionized the game of basketball. The ABA implemented the three-point shot, slam dunk, and the fast pace of the up-tempo modern game. Now the new wave of innovation is hitting basketball — the Moneyball approach. The Houston Rockets have hired Daryl Morey, the NBA's first Moneyball general manager. Aside from being tall, Morey does not look the part. He has not played basketball since high school, and he has never been a coach or scout. What  Morey does have is a commitment to statistical analysis and an owner who has invested millions to help him pursue it. He made a series of crucial additions to the Rockets roster in a string of Billy Beane-like moves. Although the Rockets lost in the first round of the playoffs, they reeled off a 22-game winning streak during the regular season, the second longest in NBA history. Morey may not have the flare and style of the ABA, but he may be just as influential.

Morey does have is a commitment to statistical analysis and an owner who has invested millions to help him pursue it. He made a series of crucial additions to the Rockets roster in a string of Billy Beane-like moves. Although the Rockets lost in the first round of the playoffs, they reeled off a 22-game winning streak during the regular season, the second longest in NBA history. Morey may not have the flare and style of the ABA, but he may be just as influential.On to my MoneyLaw point. Last month's issue of the American Bar Association Journal features a segment called Making the Case for Change. The segment contains several short articles from lawyers and judges arguing for changes in litigation in federal courts. Two articles in particular state that clients are best served when you make efforts to get along with opposing counsel and when you behave in a professional, civil manner toward opposing counsel. The authors of these articles are somewhat unlikely sources: Stephen Susman (the G-Man) and Barry Barnett of Susman Godfrey, and Michael Keating of Foley Hoag. These are BigLaw partners, the ones we would expect to espouse the virtues of hardball tactics to incessantly fight over every inch in litigation.

Read the rest of this post . . .In particular, Susman and Barnett observe that communication with opposing counsel can eliminate needless discovery fights and motion practice, which culminates in benefits for both the client and the court. I could not agree more. What bothers me is that civility and professionalism are viewed as innovative thinking in the modern era of legal practice. the not so distant past, these were the hallmarks of our profession. As former California Bar Association president Sheldon Sloan put it discussing a task force on civility, "The civility that used to exist has dissipated. A lot of lawyers don't know how to behave."

I think a significant part of the problem is that a growing number of lawyers subscribe to the notion that you can intimidate the opposition into a favorable result for the client. They feel you can intimidate with tactics such as refusing to agree on scheduling or deadlines, berating opposing counsel at every opportunity, filing needless motions and being disrespectful to witnesses. California Court of Appeals Justice Richard D. Fybel put it best in this article: "Intimidation is overrated as a litigation tool. It does not work in the widest range of my experience--from business cases to criminal pleas and trials."

Even if you disagree with Justice Fybel and put stock in intimidation tactics, the added benfits better exceed the additional costs imposed on the client. Every intimidation tactic adds unnecessary billable hours which, when compounded over the hundreds (or thousands) of tasks involved in litigation, adds up to an extraordinary expense with no real rate of return. The only intimidation that works is thorough knowledge of the case and skillful courtroom presentation.

Classroom Access and the "5 Whys"

I considered giving this post an Onion-like title, something to the effect of "UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW SCHOOL PROPOSES LEAD DOME OVER HYDE PARK; DEAN LEVMORE DERIDES CITY-WIDE WIRELESS  HOT SPOT AS 'ANTI-INTELLECTUAL.'" But Legal Profession Blog is a serious blog (the ABA Journal's blog

HOT SPOT AS 'ANTI-INTELLECTUAL.'" But Legal Profession Blog is a serious blog (the ABA Journal's blog

regularly uses Mike Frisch's posts as source material!) So I'll try a moderately serious response.

As has been noted in the blogosphere over the last day or so, Chicago has decided to shut off wireless internet access to its classrooms. Ian Ayres applauds this move; Calvin Massey is skeptical. I tend to side with Calvin for the reasons he gives over at The Faculty Lounge, but I want to expand.

As Calvin notes, if the teaching is sub-par, students will find different ways of checking out. I have done the New York Times crossword regularly going nigh on thirty years, and it all started in the back row of the classrooms at Stanford Law School, courtesy of the Stanford Daily's syndicated use of the puzzle. I won't say which classes, but, trust me, there were some whose combination of turgid text and stultifying pedagogy earned my ennui many times over.

Insulating the classroom from the current iteration of technology is a piece of chewing gum in a crumbling dike. It's only a matter of time until there is universally available city-wide wireless access (I think Boston has been talking about it.) At which point, the construction of the lead dome will be necessary to avoid surfing unless the solution is indeed to start us on the road back to quill pens and inkwells by banning laptops in the classroom.

It seems to me that schools ought to be at least as forward-thinking as manufacturing companies in avoiding the quick fix in favor of getting at the root cause. In modern Japanese-developed lean manufacturing (kai-zen or continuous improvement), one principle used in analyzing the cause of defects is the "five whys": you don't truly get to the root cause of a problem unless you ask why, get an answer, and then ask why about the answer five times. Using the five whys here would tell us, I think, that we haven't solved the surfing problem by constructing a technology shield.

Wait a minute. Five whys. Gosh, that sounds almost . . . Socratic!

California Joins Massachusetts In Finding Right to Same-Sex Marriage

The 4-3 majority opinion by the California Supreme Court has resulted from a case with quite a different procedural and substantive history than that of our own historic Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decision declaring a right to same-sex marriage here nearly five years ago. For more on the history and the story leading up to the California decision released today, and for a link to video of the oral arguments before the court in this case, see my last post on this topic, Oral Arguments Heard in California Same-Sex Marriage Case.

But the California ruling will have much the same effect in California as the Massachusetts ruling had here: within a month, gay and lesbian couples all throughout California will be permitted to marry. Gay and lesbian Californians will no longer have to settle simply for domestic partnerships.

As a result, California now joins Massachusetts as the second state in the nation to recognize, based on its own state constitution, the full right of gay and lesbian couples to the institution of marriage. Now, we should have our eyes on Connecticut, where another important decision should be coming soon.

For information about Massachusetts divorce and family law, see the divorce and family law page of my law firm website.

Legal Education from the Demand Side

I recently got that sort of opportunity thanks to Chapman Law School's "Employment Blitz," a special event where faculty and alums try to help graduating students find jobs. We brought our rolodexes, laptops, and cellphones to a large room filled with desks and phones, met one-on-one with resumé-toting students, and started making calls. The experience gave me a newfound—or perhaps I should say, "long forgotten"—appreciation of the perils and promises of trying to land an entry-level law job.

To their credit, the graduating students showed calm resolve, and all of the acquaintances and former students that I phoned seemed eager to help. I usually got little more then tentative leads and earnest well-wishing, granted, but even that helped to lift the students' spirits. And hearing somebody reply, "Send him down to my office! I've got some work for him!" definitely made the effort worthwhile.

[Crossposted at Agoraphilia, MoneyLaw, and College Life O.C..]

Se7enth heaven

"GrumpyLaw"? Hardly. Unwarranted name-calling aside ☺ ☺ ☺ , Geoffrey Rapp deserves the highest praise for his Prawfsblawg post on the reasons that some tenured law professors give for not writing. As Lynn Baker once told me, joining issue is the highest form of intellectual flattery. So here goes. . . .

"GrumpyLaw"? Hardly. Unwarranted name-calling aside ☺ ☺ ☺ , Geoffrey Rapp deserves the highest praise for his Prawfsblawg post on the reasons that some tenured law professors give for not writing. As Lynn Baker once told me, joining issue is the highest form of intellectual flattery. So here goes. . . .Geoffrey focuses much needed attention on the motivations of tenured law professors who do not write. Evidently treating a Jeff Harrison post on the in loco parentis theory of deaning as representative of all of us "folks at

- I have nothing to say that would reinvent my field.

- No one will read it anyway.

- I object to student-edited law reviews.

- I get more satisfaction out of service and teaching.

Geoff persuasively refutes the first three rationalizations. The archaic insistence on "battleship" articles privileges purported paradigm-shifting and intellectual hedgehoggery in a discipline where normal science and multifaceted foxes enjoy plenty of room. Like Snow White, academic favor smiles on all types of scholars: Sleepy, Dopey, even Grumpy. So you're a dwarf. It doesn't matter — there are plenty of ideas to be mined. Off to work you go.

Geoff persuasively refutes the first three rationalizations. The archaic insistence on "battleship" articles privileges purported paradigm-shifting and intellectual hedgehoggery in a discipline where normal science and multifaceted foxes enjoy plenty of room. Like Snow White, academic favor smiles on all types of scholars: Sleepy, Dopey, even Grumpy. So you're a dwarf. It doesn't matter — there are plenty of ideas to be mined. Off to work you go.

Besides, who knows where the next great idea will come from or even how long it will take for other scholars to recognize its significance? Mendel's work on genetics lay fallow for decades; string theory won no adherents when it was first expounded. And what exactly is wrong with normal science, the straightforward application of known principles in pursuit of real answers to significant problems? With a brief essay published (so far) solely in electronic forums, John Duffy is about to bring down a federal statute, no fewer than 46 federal judicial appointments, and millions of dollars in patent litigation. You don't need theoretical brilliance, a big audience, or student editors to have a great impact or, for that matter, a satisfying scholarly career.

As Paul Caron realized, Geoffrey's most aggressive claim consists of a complaint about the coarseness of student-edited law reviews (whose significance he paradoxically downplays):

| [I]f the reason some don't write is because of how they feel they are treated by law reviews, maybe we as teachers and advisers of student law reviews need to do a better job of reminding them that the way they reject authors can have real effects. We should encourage them to process pieces in the way they would want the products of their own hard labor to be judged, and to treat authors — even those who submit pieces editors find lame — with respect. |  |

|

I demur. The fault, dear Geoffrey, lies not in our students, but in ourselves, in what we want and how hard we're willing to work to get it. In the rest of this post, I will describe, to the best of my ability, why some professors don't write. I will then offer some thoughts on what, if anything, the legal academy as a whole should do in response.

Read the rest of this post . . . .

The commenters on Geoffrey's post, I think, offer complete and convincing explanations for the failure to write. David Fagundes is especially persuasive. One class of nonwriters is defined according to a generational difference in law school faculty hiring that presumably is fading away. Once upon a time, but arguably no longer, law schools hired at least some professors without expecting them to write scholarship. As one commenter observed, the academy's "shift in the direction of universal expectations of scholarship amounts to changing the rules mid-game." Professors hired without scholarly expectations simply aren't going to acquire, deep into their careers, a burning desire to write.

The same can be said, I think, of the supposedly "more puzzling" category of professors "who used to write and have now stopped." Indeed, as David Fagundes observes, it's a straightforward story:

To sum up: People don't write because they'd rather do other things. Even people hired on an expectation that they should write might prefer to work — or loaf — in other ways. And since we really don't make them write, people who would rather do other things besides writing . . . do other things.You've got tenure, so you can't get fired for not writing. You don't get paid for your articles, so there's no financial incentive. You probably aren't going to have the influence and fame of Holmes or Posner, so the non-financial rewards in terms of fame are limited. So instead of spending the summer slaving over an article, why not be on a beach in Bimini? . . . [T]he intrinsic pleasure and satisfaction that legal writing brings many of us is not a reaction universally shared. And because the post-tenure incentives for writing are fairly attenuated, . . . someone who lacked that sense of intrinsic satisfaction in legal writing [can] rationally decide to focus on other professional and personal priorities.

Well, what if anything should academia do about professors who don't write? Short of embracing the impracticable, even politically suicidal, "GrumpyLaw" prescription of subjecting all nonwriters to post-tenure review as thieves and scoundrels, I can recognize at least four distinct but not mutually exclusive approaches:

1. Do nothing. At the very least, do nothing drastic. Ask nonwriters to focus on teaching, advising, outreach, and university-wide committees.

Again, I demur — well, at least in part. I am hardly staking out controversial turf: the entire academy insists on scholarly performance as a condition of tenure. Although the experiment with for-profit legal education still remains in its infancy, I suspect that even schools whose primary raison d'être is to usher students from bachelor's degree to bar exam with utmost efficiency will want their faculty members to write. It's well-nigh impossible to stay current without writing something.

That said, it is the better part of administrative wisdom to leverage the better instincts of human nature. If someone does have more time and energy for nonscholarly chores around the law school, because she or he has forsworn all scholarship, then by all means assign this colleague to productive work. Everyone likes feeling valued for something.

2. Issue nonwriters a free pass, to the extent they were hired without scholarly expectations.

This approach assigns maximum value to reliance interests and to settled expectations. It's an argument that I instinctively find unpersuasive even when applied to individual human beings and downright odious when applied to business organizations. Things change, and you always knew they could — and would. That was then; this is now. But reasonable minds do disagree, and in this instance the deeply rooted conservatism of the academy — ours after all is a profession comprised of people who eagerly sacrifice pay for lifelong job security and then, more often than not, act like intellectual cowards behind cover of tenure — would undoubtedly prevail over all contrary considerations.

This approach assigns maximum value to reliance interests and to settled expectations. It's an argument that I instinctively find unpersuasive even when applied to individual human beings and downright odious when applied to business organizations. Things change, and you always knew they could — and would. That was then; this is now. But reasonable minds do disagree, and in this instance the deeply rooted conservatism of the academy — ours after all is a profession comprised of people who eagerly sacrifice pay for lifelong job security and then, more often than not, act like intellectual cowards behind cover of tenure — would undoubtedly prevail over all contrary considerations. Here's the upshot: Once upon a time we hired law professors without asking them to write. Of late we've stopped doing that. At moments like these, those of us on the winning side of a generational divide should draw solace (and inspiration) from then-Justice William Rehnquist's dissent in Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority, 469 U.S. 528 (1985). We're younger, and our time will eventually come, if only we can avoid getting fired or blowing a cardiac gasket in the meanwhile.

Here's the upshot: Once upon a time we hired law professors without asking them to write. Of late we've stopped doing that. At moments like these, those of us on the winning side of a generational divide should draw solace (and inspiration) from then-Justice William Rehnquist's dissent in Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority, 469 U.S. 528 (1985). We're younger, and our time will eventually come, if only we can avoid getting fired or blowing a cardiac gasket in the meanwhile.3. Increase symbolic rewards for writing.

It bears remembering that academia is (mostly) a not-for-profit endeavor and that big-ticket payouts to individual faculty members — monster salaries, nominal teaching schedules, slush funds for centers and junkets — rarely if ever deliver real institutional value, at least relative to other things money can buy. (Aside: this is especially true when academic rock stars arrive at a university as matched pairs.) And nonwriters know, better than their writing counterparts often imagine, what they're missing: a rougher path to promotion, fewer trips to fun conferences and symposiums, lower levels of esteem among one's peers at home and afield. But there are ways to reward people for being intellectually curious and for acting on it. Not all of them will break your budget.

4. Work harder to avoid hiring (future) nonwriters in the first place.

This is simply the managerial equivalent of normal science: apply MoneyLaw principles on a day-to-day basis, taking care to remember that reviewing forms from the Faculty Appointments Register and scouting prospects at the AALS hiring conference are day-to-day chores. Hire no one who hasn't written something before entering the teaching market. Stress performance, not pedigree. And pay very, very close attention to candidates who seek precise numerical definitions of local thresholds for tenure. People who fret about the number of articles, pages, or words needed to clinch tenure, as if they were Democratic Party Convention delegates, tend to try to write precisely the number of articles, pages, or words they imagine to suffice for tenure. Those who succeed usually do secure tenure. And thenceforth they write like Poe's Raven: "Nevermore!"

This is simply the managerial equivalent of normal science: apply MoneyLaw principles on a day-to-day basis, taking care to remember that reviewing forms from the Faculty Appointments Register and scouting prospects at the AALS hiring conference are day-to-day chores. Hire no one who hasn't written something before entering the teaching market. Stress performance, not pedigree. And pay very, very close attention to candidates who seek precise numerical definitions of local thresholds for tenure. People who fret about the number of articles, pages, or words needed to clinch tenure, as if they were Democratic Party Convention delegates, tend to try to write precisely the number of articles, pages, or words they imagine to suffice for tenure. Those who succeed usually do secure tenure. And thenceforth they write like Poe's Raven: "Nevermore!"It should be clear by now that I endorse, with wildly variable levels of enthusiasm and significant misgivings, all four of the strategies I have outlined. I've expended great thought and effort on this whole exercise because I realized, perhaps only after I began formulating a response to Geoffrey Rapp, that the task of motivating senior faculty members to write goes to the moral heart of higher education.

Scholarship is a core responsibility held, even cherished, by most members of the academy. Indeed, the best among us do not view it as a duty, but as a privilege. If higher education were to identify its gravest sins, the complete failure to produce scholarship surely would rank among the top seven.

Here at MoneyLaw and elsewhere, I have enthusiastically endorsed Hanlon's razor, the folk aphorism that reminds us: Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity. I am now prepared to embrace an even more expansive version of Hanlon's razor. Never attribute to active sin that which can be adequately explained by inertia.

Inertia, of course, bears a striking resemblance to sloth. And sloth — alongside pride, envy, greed, gluttony, lust, and wrath — has numbered among Christianity's seven deadly sins since the Middle Ages. The definition of sloth has varied over time, however. What we now call sloth was once regarded as despair, a condition of hopeless torpor now regarded as distinct from laziness for its own sake and regarded as worthy of designation as a separate deadly sin in its own right. (Go ahead and Google the search string, despair eighth deadly sin.)

The easiest of the deadly sins to commit, in law and in academia as in the rest of life, is sloth. It often consists solely of doing what comes naturally — which is to say, nothing. Among sins, sloth reigns supreme, because this may be the lone principle of Christian metaphysics backed by a fundamental law of classical physics. Moreover, if I have learned anything about the dark art of academic administration, it is the deep and unmovable hierarchy among the deadly sins of this enterprise. It does little good to fight sloth with wrath, because inertia almost always overcomes countervailing motion. In a field whose material rewards are comparatively modest, greed is a similarly weak motivator. And as exasperating as academic sloth can be, I would sooner have a colleague who is a well-intentioned scholarly nonentity than ever again work with someone so benighted as to deserve the title of the worst law professor in America.

The easiest of the deadly sins to commit, in law and in academia as in the rest of life, is sloth. It often consists solely of doing what comes naturally — which is to say, nothing. Among sins, sloth reigns supreme, because this may be the lone principle of Christian metaphysics backed by a fundamental law of classical physics. Moreover, if I have learned anything about the dark art of academic administration, it is the deep and unmovable hierarchy among the deadly sins of this enterprise. It does little good to fight sloth with wrath, because inertia almost always overcomes countervailing motion. In a field whose material rewards are comparatively modest, greed is a similarly weak motivator. And as exasperating as academic sloth can be, I would sooner have a colleague who is a well-intentioned scholarly nonentity than ever again work with someone so benighted as to deserve the title of the worst law professor in America.

Teaching Evaluations Again

Yet, the research on student evaluations is troubling. It confirms not some connection between a professor's style and student evaluations, but an overwhelming link between those two factors. Nonverbal behaviors appear to matter much more than anything else in student ratings. Enthusiastic gestures and vocal tones can mask gobbledygook, smiles count more than sample exam questions, and impressions formed in thirty seconds accurately foretell end-of-semester evaluations. The strong connection between mere nonverbal behaviors and student evaluations creates a very narrow definition of good teaching. By relying on the current student evaluation system, law schools implicitly endorse an inflexible, largely stylistic, and homogeneous description of good teaching. Rather than encouraging faculty to use nonverbal behaviors to complement excellent classroom content, organization, and explanations, the present evaluation system largely eliminates the "dog" of substance, leaving only the "tail" of style to designate good teaching. Neither law students nor faculty benefit from such a narrow definition of good teaching." (notes deleted).This article is chuck full of summaries of experiments relating to teaching evals. My favorites are those that show a few seconds of a teacher on tape with the sound off. A group of students is then asked to evaluate the teacher on a number of measures. These evaluations -- again based on sound off seconds -- turn out to be remarkable close to the evaluations the same teachers receive at the end of a semester from their regular classes. In short, looks, movement, expressions, etc, may trump everything else. Later on in the article Professor Merritt reports on a study that seem to indicate that whatever the students are responding to has virtually nothing to do with objective measures of learning.

This leads to two questions. How would a Moneylaw school evaluate teaching? If tenure, promotions and salaries are based on student evaluations would be fair to view the process as arbitrary and capricious?

14 Common Financial Mistakes People Make and 14 Rules Most Should Follow Most of the Time

There are other kinds of "mistakes" which are made in the course of divorce - and by this, I mean there are settlement decisions, which, at least from the point of view of personal finance, seem not efficient or optimal. Divorce settlements sometimes lead to some objectively bad financial moves that are, however, quite unavoidable, as they are often related to non-financial considerations or other exigencies. I am not speaking about those kinds of "mistakes" in this post, but only about general financial management mistakes I have found couples and families to have made long before they were at the point of divorce. (Lawyerly Disclaimer: These are general observations, and of course not offered as specific advice to anyone in particular. I am your unpaid blogger, not your attorney.)

14 Common Financial Mistakes People Make

1) Have no emergency or "rainy day" fund.

2) Buy a house they cannot afford.

3) Don't save enough for retirement.

4) Consult "financial advisers" from institutions such as American Express, and actually take their advice.

5) Buy whole life insurance rather than term life insurance.

6) Take out second mortgage or equity line on their home for consumer purchases.

7) Buy annuities.

8) Pay down house or other lower interest rate debts before higher interest rate debts.

9) Buy individual stocks, or day trade, in any area outside personal area of primary expertise.

10) Buy a timeshare.

11) Borrow against retirement funds, or liquidate retirement funds.

12) Go into business, or purchase property, together with a relative other than a spouse.

13) If in serious credit card debt, pay a "debt counselor" or "credit counselor" but never consult a good bankruptcy lawyer.

14) Use credit cards to pay for everything, and keep a balance on which they pay high interest.

OK, now for my 14 Rules. These are general rules which are derived from, and correspond to, the 14 Common Mistakes above. These are rules that I believe most people should follow most of the time. If you are super wealthy or destitute, obviously these do not apply to you. These are just rules, and there are exceptions to rules. Disclaimer: as general rules, these observations of mine, of course, do not constitute specific advice for any individual. As I say in these rules themselves, all should do research themselves and take charge of their own financial future, and if possible, seek specific advice from a fiduciary who can look at their particular situations, see the big picture, and give advice tailored to their particular situations.

14 Rules Most Should Follow Most of the Time

1) Maintain an emergency fund, in money market funds, conservative bond funds, or treasury bills, that is highly liquid, and outside retirement, equal to six months of your regular living expenses.

2) Buy a house, with at least 20 percent down, only if it is in a neighborhood that is a good long-term place for you and your family to live, only if you will be living there in that particular home for at least five years, and only if it costs half, or less than half, as much as the biggest house "you can afford," as calculated by the lender. Be conservative. Your home is always more expensive, and in more ways than you think, than you initially realize. You need a cushion so you can save, and you should save not just in one piece of real estate, but in other types of investments, such as stock mutual funds. Do not be "house poor" like so many people are.

3) Save at least 20 percent of your gross income in retirement - through IRAs, 401Ks, employer pension funds, etc. Obviously, take full advantage of 401Ks especially when there is employer matching.

4) If you are getting financial advice, be sure that you are using a fiduciary, not a sales person working on commissions. Do research yourself, and find a fee-only financial adviser who is a fiduciary, and will work only for you, or do it yourself. If you can't find that kind of financial adviser - many independent, fee-only financial advisers will only work on behalf of individuals with significant assets, of $1 million or more - consult a good lawyer or just do it yourself. See Can you trust your financial adviser? By Liz Pulliam Weston- MSN Money.

5) If you have children, buy level term life insurance for a term that will extend no later than when your youngest child is 25. Don't buy any other life insurance. For the vast majority of people, whole life insurance is a bad idea; in my experience, most people who have it shouldn't. They would almost always be better off investing instead in stocks and bonds through mutual funds. I am often surprised at what I see. For example, I had a client who together with his spouse had paid around $1,000 a year for only $15,000 of life insurance in their children's names to cover the children's burial expenses! Of course this horrible idea had been sold to that client by a sleazy "financial adviser" working on commission. That money would have bought that client at least an extra million dollars of term life insurance. If you really like insurance, and depending on your circumstances, after taking care of term life insurance needs, you should instead buy disability insurance. In fact, for many, that will be an even more important move than buying term life insurance. If you don't have children, or other dependents, you should only think about disability insurance.

6) If you can't afford to pay for consumer purchases, including new cars, boats, vacations, or other things, from your current regular streams of income, do not buy them. Do not take out a second loan on your home to do so. See Rule 2 and Rule 14.

7) Don't buy annuities. Only rarely are these worthwhile. If provided by an employer, fine, but don't buy them. These are usually bought because of sales commissions. See Rule 4. Instead, invest wisely, and diversify, in mutual funds for the long haul. Buy and hold. I favor index funds with low expenses, such as Vanguard funds. One example: Lots in large cap (S&P 500), some in small and midcap, and some in international. See again Rule 3.

8) Pay down highest interest rate debts, such as credit cards, first before you pay down other debts. You should always, of course, make timely payments on your loans when due, but do not pay extra to reduce the principal debt if there are other debts you have with higher interest rates. However, if you are a sure candidate for bankruptcy, you should sometimes in fact stop paying high interest unsecured debts, like credit cards, entirely. But if you think that might be the case, see a bankruptcy lawyer first before doing this. See Rule 13.

9) If you have lots of money to invest - that is, if you still have money left over after you have invested 20 percent or more of your gross income in retirement funds - you may, if you insist, invest just a small portion of your extra money in individual stocks, but only in companies in an industry about which you have more knowledge than anything else, and never the company you work for. See Rule 3 and Rule 7. I have seen too many engineers who have been burned after overconfidently, aggressively and foolishly gambling on high tech stocks or other high-risk, high-return investments. If your company provides its own stock, or stock options as benefits, fine, but if and when possible, divest as much as possible, and diversify your investments into other holdings. And generally, unless you are really as smart as Warren Buffett, you should be primarily investing in solid mutual funds rather than trying to beat the odds by picking your own individual stocks.

10) Don't buy a timeshare. Pay as you go for vacations. Ridiculous timeshares are, in my experience, the asset divorcing parties most often want the other to take, as by the time of their divorce, they often realize that they should never have bought them. And don't buy a second home, unless you can afford it - that is, you have regularly saved enough for retirement, and are continuing to save 20 percent of your gross income for retirement, have no need to save for any child's future college expenses (you have enough saved in a 529 plan or otherwise to pay for your children's college costs) and still have money left over.

11) If tempted to raid your retirement fund, which will lead to absurd penalties, find any way you can to avoid this. If you can't cut your expenses or find a way to pay for the necessary things in another way, then come up with the money by temporarily halting your present contributions to retirement (preferable), or borrowing against your retirement (if it absolutely has to be done, this is better than taking an early withdrawal, but this is still bad). This should usually not be a problem if you follow Rule 1.

12) Go into business in one of the following ways only: a) by yourself, b) with others who are not relatives - but get a detailed, written agreement- or c) not at all. When buying a house or other property that you will live in, either do this by yourself, with your spouse - yes, still risky, but this is what marriage is about - or not at all.

13) If you have a lot of high interest, unsecured debt, consult a bankruptcy lawyer to see if you can and should go bankrupt, and if not, how best to get rid of the debt you have. Again, pay down the highest interest rate debt first. Usually you will want to maintain good credit and maximize your credit score, but sometimes you should default on high interest, unsecured debt. Get out of high interest rate debts one way or another, usually by paying them off as soon as possible, unless it is feasible and appropriate for you to avoid paying back the debt, through bankruptcy or default, after consulting a bankruptcy attorney. Often bankruptcy will be a better long-term move, and your credit may actually improve in a short period of time after you eliminate outrageous debts and make a financial recovery. There are many credit counselors who do nothing for you, and just make money as the middleman between you and the horrible vultures that are known as credit card companies.

14) Buy in cash, or use your bank debit card to make purchases, and pay off credit card balances in full each month. Can't or don't want to pay for it now? Then don't buy it. See Rule 6.

******

For information about personal finance, especially in the context of divorce and family law, see some links to a few good websites and financial calculators on the links page of my law firm website.

Forget about Memorization

Alas for my students, however, SuperMemo probably won't help much with the study of law. As first-year students quickly discover—often to their evident chagrin—you cannot learn the law simply by memorizing it. SuperMemo might work for, say, drumming conjugations of French verbs into your head, but it won't help you figure out whether a promise to forego demanding payment of a debt constitutes illusory consideration. In that, the law resembles physics; learning the rules couts for far less than figuring out how to apply them to particular facts.

I don't know of any sure-fire way to package that sort of teaching. We law profs muddle along with a mixture of classroom demonstrations, abstract theorizing, rough rules-of-thumb, and hands-on practice. I'd love to offer my students something like a SuperMemo program for mastering the law, but I doubt that so complicated a task would squeeze into a neat algorithm.

[Crossposted at Agoraphilia, MoneyLaw, and College Life O.C..]

Writing, Talking, and Anonymity

The exchange on anonymous posts made me think of another small discussion on this blog about written and spoken messages. (I am not talking about the series on the (not) New York Times rule.) I took the position that a written message – even an argument – is sometimes preferable because it forces the other person to “listen” before responding. When I wrote that I had in mind conversations with colleagues and friends who, before a thought is complete, begin shaking their heads “no” and preparing a response to something they have yet to hear. Writing seems to me to be more like an approach I read about for how couples should argue. The approach required one partner to repeat back to the other person what they had said before responding so at least the response would be on point.

I think in that older discussion Marie made the point that – and she would have said it more gently than this I think but then again maybe not– if someone has got something to say to someone else they should have the guts to say it to his or her face.

That is where the connection is to the issue of anonymous postings. I will have to concede that writing as opposed to face to face, whatever I think its advantages may be, also gives the speaker just a shade of anonymity. The writer does not have to see the reaction of the other party and to some extent can be viewed as not fully accountable for the impact of what he or she says. That makes the writer seem like a coward. On the other hand, what if those visible cues given off by the person who is “listening” to something he or she does not want to hear are actually part of the way he or she argues, even a subtle form of bullying or at least a passive aggressive why of signaling disapproval? Why should the person simply delivering a message or stating a point of view accept subtextual punishment for doing so? If it has the impact of making full discussion less likely is it any different from raising one’s voice or slamming the door?

The brief exchange on writing as opposed to speaking moved me to the "it all depends position." On the other hand, if there ever was a door slammer it is the anonymous commentator. “So there!” he says as the door crashes shut. The problem with this generalization is that I can think of legitimate reasons why a commentator would like to remain unnamed. An untenured person (although I have yet to witness a case in which it would be necessary) may feel this way. Similarly, the member of any law firm or any terminable at will employee may for good reason want to remain anonymous. On the other hand, there are the anonymous commentators who are the blogging version of high school kids writing on the bathroom wall. They do not care to agree or disagree with the substance (disagreement is better from my point of view because it increases the chances of learning something). I've decided to delete those from now on. The psychology of these commentators is lost on me. How can saying something that you fight not to have attributed to you make you feel better? I have some hunches about these grown up bathroom wall markers but they are too cruel to write. I keep trying to remember that even anonymous is someone's son or daughter.

Blog Archive

- February (72)

- January (143)

- December (136)

- November (176)

- October (99)

- September (32)

- August (31)

- July (27)

- June (27)

- May (27)

- April (33)

- March (31)

- February (28)

- January (33)

- December (28)

- November (30)

- October (36)

- September (35)

- August (32)

- July (33)

- June (9)

- May (7)

- April (4)

- March (2)

- February (2)

- January (9)

- December (7)

- November (15)

- October (19)

- September (10)

- August (14)

- July (86)

- June (9)

- May (11)

- April (18)

- March (16)

- February (41)

- January (17)

- December (25)

- November (19)

- October (32)

- September (29)

- August (33)

- July (48)

- June (35)

- May (28)

- April (48)

- March (55)

- February (50)

- January (62)

- December (41)

- November (84)

- October (88)

- September (79)

- August (63)

- July (72)

- June (64)

- May (39)

- April (55)

- March (81)

- February (54)

- January (56)

- December (49)

- November (57)

- October (50)

- September (38)

- August (24)