When Child Support Doesn't Get to the Children - Another Way Our Children Are Being Left Behind

Not often can one read such an intelligent discussion of the child support collection system. This article examines a particularly troubling current nationwide failure of our child support collection system - that is, the particular failure of our child support collection system within the lower income population of child support obligors and recipients. Sadly, our current system of collecting child support on behalf of poor custodial parents, which does not simply pass on child support to poor custodial parents but funnels collected money first back to the government to reimburse the government for public assistance benefits and collection costs, has failed miserably to do what it was originally designed to do - i.e., actually support children.

As the information in the article suggests, budget and political priorities have stood in the way of reforms desperately needed to protect those who have the weakest political voice, namely the poor, both mothers and fathers, child support recipients and obligors alike. Our child support collection system, even though increasingly effective in collecting more and more money, is about as effective in helping the poor as is "No Child Left Behind" - you know, that educational national law/policy that doesn't put its money where its mouth is, gives unfunded mandates to the states, and is more appropriately called "No Child Left Untested." But of course we are told we have more important things to do, like, for example, we have a few wars to pay for right now....Class War too, you say?

"MILWAUKEE — The collection of child support from absent fathers is failing to help many of the poorest families, in part because the government uses fathers’ payments largely to recoup welfare costs rather than passing on the money to mothers and children. Close to half the states pass along none of collected child support to families on welfare, while most others pay only $50 a month to a custodial parent, usually the mother, even though the father may be paying hundreds of dollars each month. Critics say using child support to repay welfare costs harms children instead of helping them, contradicting the national goal of strengthening families, and is a flaw in the generally lauded national campaign to increase collections.... "

Lucky Jim, J.D.

Lucky Jim, J.D., a new blog, is off to a good start. One of its first posts retransmits advice from Feminist Law Professors for "particularly noxious" law teaching candidates:

Don’t be a pretentious asshole. You may well think you are too good to teach at a second tier law school, but if that is the case, why are you wasting our time and money by interviewing for a job with us?Amen, sister. Amen, brother.

To Spank or Not to Spank

The trend, throughout the US, is away from corporal punishment, even if there is no trend to outlaw it explicitly. While spanking is not clearly outlawed in Massachusetts, our case law does not clearly condone it either. And there is currently proposed legislation here that would indeed explicitly outlaw it; if the legislation is passed, Massachusetts could become the first state to prohibit parents from using corporal punishment.

I just read an interesting post on the subject in today's Massachusetts Law Updates, the Massachusetts Trial Court Law Library's blog: Spanking and the Law. Although I'm not sure a law banning parents from spanking their children is necessary or even a good idea, I am sure myself that spanking itself is a bad idea. I believe parents should act as though such a law is already in effect.

I say don't spank, first of all, because as a parent I don't believe spanking is a good means of discipline, I have never used it myself, never needed it, and never would use it. (Of course, my current aversion to spanking may have something to do with the fact that my son is now old enough and big enough to spank me back...)

Second of all, I say don't spank, because I am a divorce and family law attorney. As such, my clients are by and large parents who are in the process of getting divorced, parents who are already divorced, or parents or other parental figures in divorce, guardianship or paternity disputes. Such parents in particular often have to worry about potential or ongoing disputes with other parents or other rivals in custody and visitation matters, and it's not generally a good idea to be giving your potential enemies ammunition to use against you.

But finally, and most importantly - and this is strongly related to my own personal objection to spanking - I say don't spank because there is a fine line between physical discipline and abuse. Where there are children, there are mandated reporters. In our schools and hospitals, and elsewhere, there are officials, teachers, counselors, medics, medical and psychological professionals, who are mandated to report any suspected neglect or abuse to the Department of Social Services.

Really, it's just better not to spank. There's a better way.

Massachusetts Law Updates: Spanking and the Law

Jewel's end-of-semester benediction

As exams loom, pop singer Jewel offers a benediction worthy of any law school:

The original tune is truly lovely. Watch the video:If I could tell the class just one thing

It would be that you're all okay

And not to worry because worry is wasteful

and useless in times like these

You won't be made useless

Don't be idled with despair

You should gather yourself around your mind

for light does the darkness most fear

Faculty Citation Rankings

Following up my TaxProf Blog posts on The Most-Cited Tax Faculty and Tax as Vermont Avenue in Monopoly:

- Balkinization: Skepticism About Leiter's Citation Rankings, by Brian Tamanaha (St. John's)

- Legal History Blog: The Limits of Leiter's New Citation Study, by Mary L. Dudziak (USC)

Brian responds to each of these criticisms in:

- Once More Into the Citation Rankings Fray...

- Mary Dudziak Isn't Happy with the New Citation Rankings

See also:

- Concurring Opinions: Leiter Study Data: Concentration by School, by Jack Chin (Arizona)

- Essentially Contested America: What's Wrong with Ranking Legal Scholars?, by Robert Justin Lipkin (Widener)

- PrawfsBlawg: The Potential Pathologies of "Leiter-scores," by Ethan Leib (UC-Hastings)

Bernie Black and I discuss the pros and cons of citation rankings in Ranking Law Schools: Using SSRN to Measure Scholarly Performance, 81 Ind. L.J. 83, 92-95 (2006). We note:

[T]he literature suggests that citation counts are a respectable proxy for article quality, and correlate reasonably well with other measures. As with the other measures, however, citation counts have limitations. Some of these will average out at the school level, but not all or not fully. These include:

- Limited range of schools.

- Timing.

- Dynamism.

- Survey article and treatise bias.

- Field bias.

- Interdisciplinary and international work.

- The "industrious drudge" bias.

- "Academic surfers."

- The "classic mistake."

- Gender patterns.

- Odd results.

Our modest conclusion is that citation counts, like reputation surveys, productivity counts, and SSRN download counts, are imperfect measures that, taken together, can provide useful information in faculty rankings. For more, see TaxProf Blog.

Shaving South Carolina with Hanlon's razor

As soon as I posted my latest commentary on South Carolina's bar exam scandal (parts 1, 2, and 3), I encountered this blog post affiliated with The State Online that raises a truly demoralizing possibility that I had not considered.

As soon as I posted my latest commentary on South Carolina's bar exam scandal (parts 1, 2, and 3), I encountered this blog post affiliated with The State Online that raises a truly demoralizing possibility that I had not considered.As commenter Mike Cakora accurately observed in The State Online's discussion, I have written about South Carolina's bar exam scandal as yet another instance of "cronyism under cover of stupidity." There is simply no way, I've assumed, that the Justices of the South Carolina Supreme Court could be so illogical that they really would admit 20 failed candidates to the bar simply to create parity with one mistakenly admitted candidate. No one could be that stupid; that court must be hiding something. Surely something else is afoot, and the usual Southern political sin of corruption is the obvious candidate.

But perhaps I have forgotten something fundamental: Hanlon's razor. This folk aphorism reminds us: Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity. As I've acknowledged elsewhere, never assume malice when stupidity will suffice.

But perhaps I have forgotten something fundamental: Hanlon's razor. This folk aphorism reminds us: Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity. As I've acknowledged elsewhere, never assume malice when stupidity will suffice.There is legal support for this principle. In TXO Production Corp. v. Alliance Resources Corp., 187 W. Va. 457, 419 S.E.2d 870 (1992), aff'd, 509 U.S. 443 (1993), Justice Richard Neely of the West Virginia Supreme Judicial Court divided the world between "really stupid" and "really mean" actors. (Justice Neely was speaking of defendants who are assessed punitive damages, but his point has broader application.) The Supreme Court of the United States affirmed, see 509 U.S. at 465, in a manner of speaking. Hanlon's razor suggests that "really stupid" people outnumber and outweigh "really mean" people, that we should blame stupidity before malice.

I suppose I might be guilty of excessive reliance on a related principle, Clark's Law: incompetence, if sufficiently advanced, is indistinguishable from malice. But all this is to say that I haven't really given enough thought to the possibility that South Carolina's Supreme Court Justices sincerely believed that a single scrivener's error in bar exam grading warranted compounding that mistake by a factor of twenty.

Brad Warthen, a reporter for The State, has pondered this precise question. And what he finds is demoralizing in its own right, perhaps more so than everything I've contemplated:

Lord have mercy. If indeed this wasn't cronyism under cover of stupidity, but simply stupidity in undiluted form, perhaps South Carolina is in even worse shape than any of us might have imagined. All that said, I stand by my original assessment: Whether the powerful people who perpetrated this scandal were really mean, or really stupid, or (as I continue to believe) really mean and stupid enough to believe that the public would swallow a flamboyantly ludicrous explanation, the people of South Carolina deserve far better.What the court actually did was so nonsensical that I couldn't quite take it in from our news account. . . . As it turned out, it had done exactly what I had thought I'd read: It decided to give that one candidate a free pass on that section of the test, and then gave everybody a free pass on that section, boosting 20 demonstrably unqualified people to the status of attorney at law. . . .

There's no way that the court would turn 20 "fails" to "passes" because of a mistake on one. . . . [T]he court has a higher responsibility to the 4 million people of South Carolina.

This was a serious error in judgment, and to me, worse than any inherent harm based on who made a call to whom.

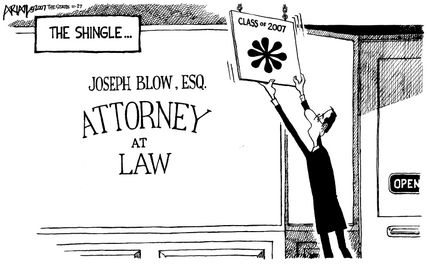

See how they run

Lost causes, upon further reflection, may not be as forlorn as they might have first appeared. Not Very Bright's survey of the South Carolina press, including op-ed columns and letters to the editor, reveals a reasonably healthy skepticism among journalists and members of the general public in that state. Despite taking extreme care not to impugn the South Carolina Supreme Court's "integrity," The State is willing to declare that the court "exercised poor judgment" in its handling of South Carolina's July 2007 bar exam. An apparent majority of The State's corresponding readers take even sharper issue with the Supreme Court. A Hilton Head newspaper has argued that the Court's "explanation" of its decision "raises more questions" than it answers. As MoneyLaw has already reported, the Greenville News argues that the Supreme Court's reasoning flunks fifth-grade logic and morality. And then there is this editorial cartoon in The State:

Lost causes, upon further reflection, may not be as forlorn as they might have first appeared. Not Very Bright's survey of the South Carolina press, including op-ed columns and letters to the editor, reveals a reasonably healthy skepticism among journalists and members of the general public in that state. Despite taking extreme care not to impugn the South Carolina Supreme Court's "integrity," The State is willing to declare that the court "exercised poor judgment" in its handling of South Carolina's July 2007 bar exam. An apparent majority of The State's corresponding readers take even sharper issue with the Supreme Court. A Hilton Head newspaper has argued that the Court's "explanation" of its decision "raises more questions" than it answers. As MoneyLaw has already reported, the Greenville News argues that the Supreme Court's reasoning flunks fifth-grade logic and morality. And then there is this editorial cartoon in The State:

The most skeptical voice in the debate, so it seems, is one Gregory Kestor, who laid down a challenge to me in the commentary to Lost Causes:

What are you, Jim Chen, Dean of the Louisville Law School, prospective Man of Destiny, going to do about it? The Gang of Five on the SC Supreme Court, is doing what Law does best: speaking power to truth. What are you going to do about it? My bet: nothing more than has appeared on this blog.Mr. Kestor, you lose. You seem to have forgotten that I, having been a "Southern boy fourteen years old," can summon "not once but whenever [I] want[] it" the spirit of that "instant when it's still not yet two o'clock on that July afternoon in 1863." Ambition and action, one and inseparable, now and forever. I'll take my stand.

I think that the good people of South Carolina, supported by lawyers and believers in the rule of law everywhere, are looking for some way to salvage something good from this shameful episode. I believe that the answer lies in holding each of these jurists accountable for their decision to admit one and twenty concededly unqualified individuals to the South Carolina bar:

- Chief Justice Jean Hoefer Toal

- Justice James E. Moore

- Justice John H. Waller

- Justice Costa M. Pleicones

- Justice Donald W. Beatty

The members of the Supreme Court shall be elected by a joint public vote of the General Assembly for a term of ten years, and shall continue in office until their successors shall be elected and qualified, and shall be classified so that the term of one of them shall expire every two years. . . .South Carolinians who are willing to hold their Supreme Court Justices accountable have no direct recourse at the ballot box. They must rely on members of the General Assembly to do their work. One of the chief players in this morality play, the Judiciary Committee chairman, is unlikely to take any action that would imperil the Supreme Court seats of the Justices who ordered his daughter admitted to the bar.

Fortunately, what Neil Young told Alabama nearly four decades ago is equally true for South Carolina: "You've got the rest of the union / to help you along." The problem of a powerful body whose members enjoy long terms and are themselves elected by some other legislative entity is a familiar one in American history. The original United States Constitution of 1787 did not permit the direct election of United States Senators. Rather, members of the Senate were "chosen by the Legislature" of each state. A 1914 amendment to the Constitution fixed this problem. The Seventeenth Amendment restates the first paragraph of Article I, section 3 of the Constitution and provides for the election of senators by replacing the phrase "chosen by the Legislature thereof" with "elected by the people thereof":

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures. . . .What we now need is a comparable amendment to the South Caroina Constitution.

Imagine this revision of Article V, § 3 of South Carolina's constitution:

The members of the Supreme Court shall be elected byReplacing the existing phrase, "a joint public vote of the General Assembly," with these words, "the qualified electors of the State," is enough to transform the South Carolina Supreme Court into a body chosen directly by the voters of South Carolina. I've recommended a halving of the Justices' terms, strictly on the sense that a decade is an extremely long time for anyone to serve, with no accountability besides impeachment, on a putatively democratic tribunal.a joint public vote of the General Assemblythe qualified electors of the State for a term oftenfive years, and shall continue in office until their successors shall be elected and qualified, and shall be classified so that the term of one of them shall expire everytwo yearsyear. . . .

Of course, the primary method for amending South Carolina's constitution, Article XVI, § 1, itself requires the cooperation of the General Assembly:

Any amendment or amendments to this Constitution may be proposed in the Senate or House of Representatives. . . . The amendment may delete, revise, and transpose provisions from other articles of the Constitution provided the provisions are germane to the subject matter of the article being revised or being proposed. If it is agreed to by two-thirds of the members elected to each House, the amendment or amendments must be entered on the Journals respectively, with the yeas and nays taken on it and must be submitted to the qualified electors of the State at the next general election for Representatives. If a majority of the electors qualified to vote for members of the General Assembly voting on the question vote in favor of the amendment or amendments and a majority of each branch of the next General Assembly, after the election and before another, ratify the amendment or amendments, by yeas and nays, they become part of the Constitution. The amendment or amendments must be read three times, on three several days, in each House.Why do I think South Carolina's General Assembly would amend the state constitution when I concede that they are unlikely to be responsive to direct challenges to the incumbent members of the Supreme Court? Because the case for reforming the Supreme Court's structure is worthy and can — and should — be advanced without reference to this year's bar exam scandal. I'll couch this sentiment in language that the Justices themselves would recognize and, mutandis mutandi, very recently adopted as their own:

No consideration will be given to the identity of any Justice who would stand to suffer from this action. Moreover, this action is not influenced by any appeal, campaign, or public or private outcry. It is simply deemed the best choice among several alternatives.All together now, South Carolina. Make your Supreme Court Justices stand for election. See how they run.

Coontz v. Marquardt on "Taking Marriage Private"

Do we need a new way to assign legal benefits and responsibilities for partners that used to be available only through traditional marriage, now that we have so many different alternative forms of domestic relationships and partnerships, both gay and straight, some legally sanctioned and others not? Chew on these two opinion pieces if you're interested in this oh-so-current issue.

Hague Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support

"Delegates from sixty-eight States and the European Community have finalized the Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and other Forms of Family Maintenance at the 21st Diplomatic Session of the Hague Conference on Private International Law.

Basically, the states that ratify the convention agree to assist citizens from other states who have also ratified the convention to recover child support.

The United States immediately signed the Convention, the first (and, thus far, only) State to do so...."

7200, Conservatively Speaking

These numbers must be off but, think about it: 180 law schools, 2 journals per school, 5 issues a year, 4 article per issue. I think that is a demand for 7200 articles per year. (72,000 since 1997) That may be conservative. (Evidently about a third of these are sent to the top 15 journals before ending up elsewhere.) Surely the supply of useful articles is not that high. In fact, I have never heard of an article that did not find a home although I have flirted with that possibility at least twice.

Would a Moneylaw school require as much writing as is currently the case? Maybe. There are some explanations for the current level. I used to support maximum writing by viewing law professors as scientists. They experiment with articles, never knowing until some time in the future which ones "work." Irrelevant today might be highly relevant in 10 years. Just keep the ideas flowing and eventually, "boom," a winner. After all, if there is too much writing, who would be told to stop? How do we know in advance who will not produce something wonderful? Then I realized that a great deal of legal scholarship in not a search for answers but advocacy for one cause or another restated in twenty different ways. At least for me, the research-lab-scientist explanation lost its traction.

Ok, so maybe the writing is to give the students something do to. To some extent, the proliferation of reviews is a response to student demand. If that is the case, what skills are taught and why do only some students get to do it?

Finally, maybe writing is a test -- a rationing mechanism. There are way too many people who want to be law professors so the positions are allocated to those willing to write. If it is only a rationing mechanism, then I and others should stop complaining about post tenure non writers.

I think there is some historical explanation for all of this that I probably should know. Or maybe the high levels of demand and supply are explained by the last two factors above. Still, what would a Moneylaw school's approach to writing be?

I Blame The Hierarchy

The presentation and panel went really well, I thought. The Candidate is one of the giants of his/her field (I am not indulging in hyperbole here) and is a up for a lateral tenured position from an extremely high ranked law school to our more modestly high ranked law school. It may be like, climbing a step or so down from a ladder, but because we are in Awesome Part of the Country with a particularly strong set of faculty in his/her area, well, the move has all sorts of subjective considerations. It would be a big coup for our school, which already has excellent faculty in this subject area. No, I cannot be more specific than this, it is, like all academic subfields, a small community.

This wasn't the first time I sat in on a faculty colloquium paper talk--at my last law school and this one, they are always open to students. Occasionally students participate in the Q&A, which I think is really cool. The paper talk last week was interesting and presented a novel framework, and the questions asked by the faculty (four of whom wrote in The Candidate's area) generated great discussion. The students, typically cowed by authority, kept quiet this time around.

What is different about Liberal College Law is that students are allowed a separate meeting with the faculty candidates. There's a formal committee for this, and all of their meetings are open to all of the students. This is not an interview per se, but students ask the candidates questions about their scholarship, their teaching interests, views on mentorship and interest in supervision of student research and advisorship of student organizations, etc. Feedback is then given to the school's Faculty Hiring Committee.

It's a neat feature of our school. I can imagine such talks going very badly if the students ask insensitive or dumb questions (yes, there are such things), but the questions asked were very good. This Candidate in particular drew out the J.D./Ph.D grad students, and so questions were asked about the paper's central thesis that were as good as questions asked by other faculty. That generated some interesting discussion. And further questions about The Candidate's attitudes towards academic and institutional obligations were good: I think it is fair of students to ask how interested a potential faculty is in teaching a certain course that the law school typically farms out to adjuncts; as well as the Candidate's willingness to supervise student research given that our school is trying to produce more academics.

Students have particular institutional needs from their faculty: while I don't endorse a students-as-consumers model, I do think that students have every right to certain academic expectations: good, fair, "tough" teaching; a certain degree of mentoring (case-by-case basis; the student receives what s/he invests, e.g. not letters of rec on demand, but letters of rec on merit) and support. Faculty should be open to being a part of their institution by supervising student projects and advising student groups and journals and attending to curricular gaps if they can. I know that faculty are already overstretched by their scholarship demands, teaching loads, and committee and administrative work, but you are there to teach and be a part of the life of the school. That means interacting with the students inside and outside of the classroom.

In sum, I think that students do have an important role to serve in the selection of faculty candidates. I hope that our feedback is taken seriously, and am not so cynical as to think that all of our reviews are discarded. If anything, at least the students got a chance to talk to The Candidate, who is now apprised of the students' questions and concerns. That is not without intrinsic value. Students are the life and blood of a school, and their particular needs and ideas should not be disregarded.

Interestingly, this post comes on the heels of another post by Rick Garnett asking whether students should participate in dean selection committees. I participated in a panel to select the new dean of my old school, and found the experience valuable. And so yes, I think that students should be a part of the process. For all the above mentioned reasons, students should have a certain degree of input into who teaches them and who is the steward of their school.

All I really need to know I learned in fifth grade

This column, State Supreme Court fails test on the "Facts of Life," appeared in Friday's edition of The Greenville (S.C.) News:

When I was in fifth grade, my teacher gave us a test on what he called "The Facts of Life." It consisted of simple questions, most of which I don't recall. They were on the order of:This is a simple and persuasive summary of South Carolina's bar exam scandal (MoneyLaw coverage: parts 1, 2, and 3; see also Not Very Bright's superb overview). I tip my hat, once again, to Not Very Bright.

"How many minutes are in an hour?"

"Who was the first president of the United States?"

One of them I do remember was, "How many nickels are in a dollar?"

I beamed with pride when Mr. Gelhar announced I was the first in the class to get a perfect score on that test as he graded them at the front of the room. I walked to his desk, fetched my graded paper and took it back to my chair where I reviewed my answers, reveling in the glory of that perfect score. Until, that is, I got to my answer to how many nickels were in a dollar: 50. In the rush of grading the papers as we turned them in, my teacher had accidentally marked that incorrect answer as being correct.

I can't remember what the consequences of my error were, or even if I admitted that the grading was wrong. But I do know this much: If the S.C. Supreme Court had been grading those papers, everyone in the class would have been given a pass on that question. . . .

So, if I read this right, because one person was inadvertently passed, 20 people who legitimately did not pass were given a free pass to become lawyers. That's no knock on the 20: The bar exam is intentionally difficult, and not passing it is nothing to be ashamed of. Test takers are allowed to try again.

But it seems almost inexcusable that the court would say that because one person's exam was recorded wrong, 20 whose exams were recorded correctly (as failures) would be allowed to pass.

ABA General Practice, Solo and Small Firm Division American Bar Association

Chairs - Kenneth Vercammen, Edison, NJ and Jay Foonberg, Beverly Hills, CA

In this issue:

1. USING THE AHLBORN DECISION TO REDUCE A MEDICAID LIEN

2 EXECUTOR OF A WILL- DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

3. BALANCE BILLING between the Medicaid program and the Medicare program.

4. WE PUBLISH YOUR FORMS AND ARTICLES

1. USING THE AHLBORN DECISION TO REDUCE A MEDICAID LIEN

By: Thomas D. Begley, Jr., Esquire

What could be done when the Medicaid lien is so large that it would consume all or a substantial portion of the recovery.

A recent United States Supreme Court case has provided personal injury attorneys with ammunition to reduce a Medicaid lien in a personal injury case so that the payment to the State Medicaid Agency is fair and reasonable. After a series of cases around the country divided on the issue as to whether the State Medicaid Agency may recover from that portion of a settlement not earmarked for past medical expenses the United States Supreme Court decided the issue in the Ahlborn case,[1]The Court held that federal law requires states to ascertain the legal liability of third parties and to seek reimbursement for medical assistance to the extent of such legal liability. The state is considered to have acquired the rights of the injured party to payment by any other party for such health care items or services. As a condition of Medicaid eligibility, the individual is required to assign to the state any rights to payment for medical care from any third party. The Arkansas statute required that if the lien exceeds the portion of the settlement representing medical costs, satisfaction of the lien requires payment out of proceeds meant to compensate the recipient for damages distinct from medical costs, such as pain and suffering, lost wages, and loss of future earnings.

In the Ahlborn case, the plaintiff was involved in an automobile accident. Medicaid paid $215,645.30 on her behalf. Plaintiff filed suit for past medical costs and for other items, including pain and suffering, loss of earnings and working time, and permanent impairment of her future earning ability. The case was settled for $550,000, which was not allocated between categories of damages. The parties stipulated that the settlement amounted to approximately 1/6th of the reasonable value of Ahlborn’s claim. The court stated that the federal requirement that states “seek reimbursement for medical assistance to the extent of such legal liability” refers to the legal liability of third parties to pay for care and services available under the plan.” Here, because the plaintiff received only 1/6th of her overall damages, the right of the state of Arkansas was limited to 1/6th of the past medical claim or $35,581.47.

The court also held that 42 U.S.C. §1396p(a)(1) prohibits states from imposing liens “against the property of any individual prior to his death on account of medical assistance paid...on his behalf under the state plan.” This prevents the state from attaching the non-past medical portion of the settlement. As a result of this ruling, states can assert a Medicaid lien only against that portion of a settlement earmarked for past medical expenses. The state may not recover against non-medical expense claims, such as pain and suffering, loss or earnings and permanent loss of future earnings. Needless to say, it is good practice in a personal injury settlement to make a clear allocation of damages.

Allocation is not only important, but must be fair. As Justice Stevens said in the Ahlborn opinion, “Although more colorable, the alternative argument that a rule of full reimbursement is needed generally to avoid the risk of settlement manipulation also fails. The risk that parties to a tort suit will allocate away the state’s interest can be avoided either by obtaining the state’s advanced agreement to an allocation or, if necessary, by submitting the matter to a court for a decision.”

Copyright 2007 by Begley & Bookbinder, P.C., an Elder & Disability Law Firm with offices in Moorestown, Stone Harbor and Lawrenceville, New Jersey and Oxford Valley, Pennsylvania and can be contacted at 800-533-7227. The firm services southern and central New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. Tom Begley Jr. is one of the speakers with Kenneth Vercammen at the NJ State Bar Association's Annual Nuts & Bolts of Elder Law and co-author with Kenneth Vercammen, martin Spigner and Kathleen Sheridan of the 400 plus page book on Elder Law.

The Firm provides services in connection with protecting assets from nursing home costs, Medicaid applications, Estate Planning and Estate Administration, Special Needs Planning and Guardianships. If you have a legal problem in one of these areas of law, contact Begley & Bookbinder at 800-533-7227.

2 EXECUTOR OF A WILL- DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Compiled by Kenneth A. Vercammen, Esq.

Providing service to worried clients who are not familiar with the legal requirements is important to Elder Law attorneys. The following short article can be revised and sent to your clients who are executors or administrators of estates.

The procedures in an Estate Administrat0ion may take from six months to several years, and a client’s patience may be sorely tried during this time. However, it has been our experience that clients who are forewarned have a much higher tolerance level for the slowly turning wheels of justice. The following a is portion of the details you may wish to inform clients who are executor after you have been retained:

Duty of Executor in Probate Estate Administration

1. Conduct a thorough search of the decedent's personal papers and effects for any evidence which might point you in the direction of a potential creditor;

2. Carefully examine the decedent's checkbook and check register for recurring payments, as these may indicate an existing debt;

3. Contact the issuer of each credit card that the decedent had in his/her possession at the time of his/ her death;

4. Contact all parties who provided medical care, treatment, or assistance to the decedent prior to his/her death;

Your attorney will not be able to file the NJ inheritance tax return until it is clear as to the amounts of the medical bills. Medical expenses can be deducted in the inheritance tax.

Under United States Supreme Court Case, Tulsa Professional Collection Services, Inc., v. Joanne Pope, Executrix of the Estate of H. Everett Pope, Jr., Deceased, the Personal Representative in every estate is personally responsible to provide actual notice to all known or "readily ascertainable" creditors of the decedent. This means that is your responsibility to diligently search for any "readily ascertainable" creditors.

Other duties/ Executor to Do

Bring Will to Surrogate

Apply to Federal Tax ID #

Set up Estate Account at bank (pay all bills from estate account)

Pay Bills

Notice of Probate to Beneficiaries (Attorney can handle)

If charity, notice to Atty General (Attorney can handle)

File notice of Probate with Surrogate (Attorney can handle)

File first Federal and State Income Tax Return [CPA- ex Marc Kane]

Prepare Inheritance Tax Return and obtain Tax Waivers (Attorney can handle)

File waivers within 8 months upon receipt (Attorney can handle)

Prepare Informal Accounting

Prepare Release and Refunding Bond (Attorney can handle)

Obtain Child Support Judgment clearance (Attorney will handle)

Let's review the major duties involved-

In General. The executor's job is to (1) administer the estate--i.e., collect and manage assets, file tax returns and pay taxes and debts--and (2) distribute any assets or make any distributions of bequests, whether personal or charitable in nature, as the deceased directed (under the provisions of the Will). Let's take a look at some of the specific steps involved and what these responsibilities can mean. Chronological order of the various duties may vary.

Probate. The executor must "probate" the Will. Probate is a process by which a Will is admitted. This means that the Will is given legal effect by the court. The court's decision that the Will was validly executed under state law gives the executor the power to perform his or her duties under the provisions of the Will.

An employer identification number ("EIN") should be obtained for the estate; this number must be included on all returns and other tax documents having to do with the estate. The executor should also file a written notice with the IRS that he/she is serving as the fiduciary of the estate. This gives the executor the authority to deal with the IRS on the estate's behalf.

Pay the Debts. The claims of the estate's creditors must be paid. Sometimes a claim must be litigated to determine if it is valid. Any estate administration expenses, such as attorneys', accountants' and appraisers' fees, must also be paid.

Manage the Estate. The executor takes legal title to the assets in the probate estate. The probate court will sometimes require a public accounting of the estate assets. The assets of the estate must be found and may have to be collected. As part of the asset management function, the executor may have to liquidate or run a business or manage a securities portfolio. To sell marketable securities or real estate, the executor will have to obtain stock power, tax waivers, file affidavits, and so on.

Take Care of Tax Matters. The executor is legally responsible for filing necessary income and estate-tax returns (federal and state) and for paying all death taxes (i.e., estate and inheritance). The executor can, in some cases be held personally liable for unpaid taxes of the estate. Tax returns that will need to be filed can include the estate's income tax return (both federal and state), the federal estate-tax return, the state death tax return (estate and/or inheritance), and the deceased's final income tax return (federal and state). Taxes usually must be paid before other debts. In many instances, federal estate-tax returns are not needed as the size of the estate will be under the amount for which a federal estate-tax return is required.

Often it is necessary to hire an appraiser to value certain assets of the estate, such as a business, pension, or real estate, since estate taxes are based on the "fair market" value of the assets. After the filing of the returns and payment of taxes, the Internal Revenue Service will generally send some type of estate closing letter accepting the return. Occasionally, the return will be audited.

Distribute the Assets. After all debts and expenses have been paid, the executor will distribute the assets. Frequently, beneficiaries can receive partial distributions of their inheritance without having to wait for the closing of the estate.

Under increasingly complex laws and rulings, particularly with respect to taxes, in larger estates an executor can be in charge for two or three years before the estate administration is completed. If the job is to be done without unnecessary cost and without causing undue hardship and delay for the beneficiaries of the estate, the executor should have an understanding of the many problems involved and an organization created for settling estates. In short, an executor should have experience

At some point in time, you may be asked to serve as the executor of the estate of a relative or friend, or you may ask someone to serve as your executor. An executor's job comes with many legal obligations. Under certain circumstances, an executor can even be held personally liable for unpaid estate taxes. Let's review the major duties involved, which we've set out below.

In General. The executor's job is to (1) administer the estate--i.e., collect and manage assets, file tax returns and pay taxes and debts--and (2) distribute any assets or make any distributions of bequests, whether personal or charitable in nature, as the deceased directed (under the provisions of the Will). Let's take a look at some of the specific steps involved and what these responsibilities can mean. Chronological order of the various duties may vary.

Probate. The executor must "probate" the Will. Probate is a process by which a Will is admitted. This means that the Will is given legal effect by the court. The court's decision that the Will was validly executed under state law gives the executor the power to perform his or her duties under the provisions of the Will.

An employer identification number ("EIN") should be obtained for the estate; this number must be included on all returns and other tax documents having to do with the estate. The executor should also file a written notice with the IRS that he/she is serving as the fiduciary of the estate. This gives the executor the authority to deal with the IRS on the estate's behalf.

Pay the Debts. The claims of the estate's creditors must be paid. Sometimes a claim must be litigated to determine if it is valid. Any estate administration expenses, such as attorneys', accountants' and appraisers' fees, must also be paid.

Manage the Estate. The executor takes legal title to the assets in the probate estate. The probate court will sometimes require a public accounting of the estate's assets. The assets of the estate must be found and may have to be collected. As part of the asset management function, the executor may have to liquidate or run a business or manage a securities portfolio. To sell marketable securities or real estate, the executor will have to obtain stock power, tax waivers, file affidavits, and so on.

Take Care of Tax Matters. The executor is legally responsible for filing necessary income and estate-tax returns (federal and state) and for paying all death taxes (i.e., estate and inheritance). The executor can, in some cases be held personally liable for unpaid taxes of the estate. Tax returns that will need to be filed can include the estate's income tax return (both federal and state), the federal estate-tax return, the state death tax return (estate and/or inheritance), and the deceased's final income tax return (federal and state). Taxes usually must be paid before other debts. In many instances, federal estate-tax returns are not needed as the size of the estate will be under the amount for which a federal estate-tax return is required.

Often it is necessary to hire an appraiser to value certain assets of the estate, such as a business, pension, or real estate, since estate taxes are based on the "fair market" value of the assets. After the filing of the returns and payment of taxes, the Internal Revenue Service will generally send some type of estate closing letter accepting the return. Occasionally, the return will be audited.

Distribute the Assets. After all debts and expenses have been paid, the distribute the assets with extra attention and meticulous bookkeeping by the executor. Frequently, beneficiaries can receive partial distributions of their inheritance without having to wait for the closing of the estate.

Under increasingly complex laws and rulings, particularly with respect to taxes, in larger estates an executor can be in charge for two or three years before the estate administration is completed. If the job is to be done without unnecessary cost and without causing undue hardship and delay for the beneficiaries of the estate, the executor should have an understanding of the many problems involved and an organization created for settling estates. In short, an executor should have experience.

www.centraljerseyelderlaw.com

3. BALANCE BILLING between the Medicaid program and the Medicare program.

By: Thomas D. Begley, Jr., Esquire

There is a significant difference on the issue of balance billing between the Medicaid program and the Medicare program.

1. Medicaid. Medicaid reimbursement rates are very low and as a result it is often difficult to obtain services because providers refuse to accept Medicaid. It is not possible for the patient to pay the difference between the private pay rate and the Medicaid pay rate. This is known as balance billing. Medicaid participating providers must accept the Medicaid payment as “payment in full.”[1] This means that providers accepting Medicaid waive their right to bill Medicaid beneficiaries for any amounts over the Medicaid payment.

Several states have refused to allow providers to assert liens against Medicaid beneficiaries where there is clear third party liability and the Medicaid beneficiary has obtained a significant tort recovery.

In Illinois,[2] the hospital brought an action against the Medicaid agency to allow it to refund the Medicaid reimbursement so that it could sue the Medicaid beneficiary who had obtained a substantial tort judgment. The Seventh Circuit held that the hospital could not refund the Medicaid payment to the Medicaid agency and sue the Medicaid beneficiary. The Court noted, “Medicaid is a payer of last resort.” The state can seek reimbursement from third parties, but private providers may not.

In a similar case in Florida,[3] the hospital placed a lien on the settlement award, but the court held that when a Medicaid patient obtains a tort recovery in excess of the medical expenditures paid by Medicaid, that recovery is meant to go to the injured party, not the provider. A similar result was reached in another Florida case.[4]

A federal appellate court has found that a hospital’s lien on the proceeds of a malpractice settlement was invalid and unenforceable because the hospital had already accepted Medicaid payments for the care provided to the patient.[5] “By accepting Medicaid payments, Spectrum waived its right to its customary fee for services provided to Bowling...” “Although Medicaid rates are typically lower than a service provider’s customary fees, medical service providers must accept state-approved Medicaid payment as payment in full and may not require that patients pay anything beyond that amount.”

California invalidated two state statutes authorizing provider liens against Medicaid beneficiaries.[6] The statutes authorized providers to file liens against recoveries obtained by Medicaid beneficiaries even after the provider received Medicaid. The court found that the state statutes were preempted by federal legislation banning balance billing.

2. Medicare. Previously, Medicare had a prohibition against billing Medicare beneficiaries in excess of the payment made by Medicare. Participation has been limited to providers who agreed to accept Medicare as payment in full. Recent changes in the Medicare law[7] now permit a provider to bill a Medicare beneficiary or assert a lien against the beneficiary's recovery obtained from the tortfeasor by way of settlement or award.[8]

In the seminal case,[9] a hospital sought to recover from the Medicare patient more than it received from Medicare reimbursement. The 1st Circuit held that the fact that the patient recovered more than Medicare reimbursed the hospital did not entitle the hospital to charge the patient the difference between its full fee and Medicare's lower flat fee. The agreement between Medicare and the hospital was that in exchange for Medicare guaranteeing payment to the hospital, there would be no additional payment required from the Medicare beneficiary.

The recent changes now allow providers to bill the liability insurer or place a lien against the Medicare beneficiary's recovery.

142 U.S.C. §1396a(a)(25)(c); 42 C.F.R. §447.15; 42 U.S.C. §1320a-7b(d) .

2 Evanston Hospital v. Hauck, 1 F.3d 540 (7th Cir. 1993).

3 Mallo v. Public Health Trust of Dade County, 88 F.Supp.2d 1376 (S.D. Fla. 2000).

4 Public Health Trust of Dade County v. Dade County School Board, 693 So.2d 562 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1996).

5 Spectrum v. Bowling, 410 F.3d 304 (6th Cir. 2005).

6 Olszewski v. Scripps Health, 135 Cal. Rptr. 2d 1 (Cal. 2003).

7 68 Fed. Reg. 43940 (July 25, 2003).

8 42 C.F.R. 411.54(c)(2).

9 Rybicki v. Hartley, 782 F.2d 260 (1st Cir. 1986).

Copyright 2007 by Begley & Bookbinder, P.C., an Elder & Disability Law Firm with offices in Moorestown, Stone Harbor and Lawrenceville, New Jersey and Oxford Valley, Pennsylvania and can be contacted at 800-533-7227. The firm services southern and central New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. Tom Begley Jr. is one of the speakers with Kenneth Vercammen at the NJ State Bar Association's Annual Nuts & Bolts of Elder Law and co-author with Kenneth Vercammen, martin Spigner and Kathleen Sheridan of the 400 plus page book on Elder Law.

The Firm provides services in connection with protecting assets from nursing home costs, Medicaid applications, Estate Planning and Estate Administration, Special Needs Planning and Guardianships. If you have a legal problem in one of these areas of law, contact Begley & Bookbinder at 800-533-7227.

_______________________

4. WE PUBLISH YOUR FORMS AND ARTICLES

To help your practice, we feature in this newsletter edition a few forms and articles PLUS tips on marketing and improving service to clients. But your Editor and chairs can't do it all. Please mail articles, suggestions or ideas you wish to share with others in our Committee.

Let us know if you are finding any useful information or anything you can share with the other members. You will receive written credit as the source and thus you can advise your clients and friends you were published in an ABA publication. We will try to meet you needs.

Send Us Your Marketing Tips

We are increasing the frequency of our newsletter. Send us your short tips on your great or new successful marketing techniques.

You can become a published ABA author. Enjoy your many ABA benefits.

Send us your articles & ideas

To help your practice, we feature in this newsletter edition a few articles and tips on marketing and improving service to clients. But your Editor and chairs can't do it all. Please send articles, suggestions or ideas you wish to share with others.

General Practice, Solo and Small Firm Division:

Elder Law Committee and the

Who We Are

The ESTATE PLANNING, PROBATE & TRUST COMMITTEE focuses on improving estate planning skills, substantive law knowledge and office procedures for the attorney who practices estate planning, probate and trust law. This committee also serves as a network resource in educating attorneys regarding Elder Law situations. We work with the Elder Law Committee to schedule programs at the ABA Annual meeting.

To help your practice, we feature in this newsletter edition a few articles and tips on marketing and improving service to clients. But your Editor and chairs can't do it all. Please send articles, suggestions or ideas you wish to share with others.

Let us know if you are finding any useful information or anything you can share with the other members. You will receive written credit as the source and thus you can advise your clients and friends you were published in an ABA publication. We will try to meet you needs.

We also seek articles on Elder Law, Probate, Wills, Medicaid and Marketing. Please send your marketing ideas and articles to us. You can become a published ABA author.

________________________________________

The Elder Law Committee of the ABA General Practice Division is directed towards general practitioners and more experienced elder law attorneys. The committee consistently sponsors programs at the Annual Meeting, the focus of which is shifting to advanced topics for the more experienced elder lawyer.

This committee also focuses on improving estate planning skills, substantive law knowledge and office procedures for the attorney who practices estate planning, probate and trust law. This committee also serves as a network resource in educating attorneys regarding Elder Law situations.

Kenneth Vercammen, Esq. co-Chair

Jay Foonberg, Beverly Hills Co-chair, Author of Best Sellers "How to

Start and Build a Law Practice" and "How to get and keep good clients', Beverly Hills, CA JayFoonberg@aol.com>

We will also provide tips on how to promote your law office, your practice and Personal Marketing Skills in general. It does not deal with government funded "legal services" for indigent, welfare cases.

KENNETH VERCAMMEN & ASSOCIATES, PC

ATTORNEY AT LAW

2053 Woodbridge Ave.

Edison, NJ 08817

(Phone) 732-572-0500

(Fax) 732-572-0030

Kenv@njlaws.com

Central Jersey Elder Lawwww.centraljerseyelderlaw.com

NJ Elder Blog http://elder-law.blogspot.com/

California EDD Free Tax Compliance Seminars for Employers

Some upcoming Southern California seminars are as follows:

Avoiding State Payroll Reporting Errors Tax Seminar, Huntington Beach 1/17/08;

Employee or Independent Contractor Tax Seminar, Anaheim 12/20/07, Huntington Beach 1/1/7/08, Santa Fe Springs 1/4/08;

How to Manage Unemployment Insurance Costs Tax Seminar, Goleta 12/5/07, Oxnard 1/25/08;

State Basic Payroll Tax Seminar, Huntington Beach 11/29/07, Santa Fe Springs 12/6/07;

State Payroll Workship Tax Seminar, Goleta 1/29/08, Huntington, Beach 12/19/07, Oxnard 1/8/08, Santa Fe Springs 11/28/07.

For a full list of EDD seminars offered throughout the year, see

http://www.edd.ca.gov/Payroll_Tax_Seminars/

What faculty governance can learn from the Cover 2

Consider Gregg Easterbrook's latest Tuesday Morning Quarterback column:

Terrell Owens and Randy Moss just cleaned the clocks of the Washington Redskins and Buffalo Bills, catching four touchdown passes apiece Sunday. Here is a possible solution when dealing with guys like Owens and Moss: Cover them!

Man-on-man, that is. Perhaps manly-man-on-manly-man. For most of the two contests in which these gentlemen ran wild, the Washington and Buffalo defenses were in some version of Cover 2, meaning zone, meaning no one had the specific responsibility to stick with Owens or Moss. In a Cover 2, the cornerbacks watch the short zone for outs and curls and the safeties watch the deep zone. The Cover 2 is often effective. Its weakness is that no one is specifically assigned to the other team's best receiver. Just as, when splitting a large-group dinner check, each diner might find it convenient to assume the next person will take care of the tip, in a Cover 2, each defensive back might find it convenient to think, "The safety will get him." The result is letting the other team's best receiver fly down the field unguarded.With Dallas leading 21-16 and the game tense, Owens ran an "up" against a Washington soft-zone look. Redskins cornerback Shawn Springs stood there and watched Owens fly past; Springs covered no one, and Owens caught a 52-yard touchdown, providing the game's winning margin. With New England leading 7-0 at Buffalo, Moss ran an "up" against a Bills soft-zone look. Buffalo cornerback Terrence McGee stood there and watched Moss fly past; McGee covered no one, and Moss caught a 43-yard touchdown, sparking what would become a rout by halftime. Randy Moss and Terrell Owens were not covered by anyone going deep. Moss' touchdown was especially ridiculous because the Bills rushed only two on that play. Nine defenders dropped into coverage, yet no one guarded Randy Moss going deep.

Nine guys available and no one guards the other team's best receiver: This sums up the it's-not-my-job flaw of the zone pass defense. And don't tell me the cornerback is supposed to let the receiver go deep so the corner can watch the flat. On both the touchdown passes cited above, there was no receiver in the flat. Both cornerbacks just stood there while the other team's star roared past them for a touchdown. Nor are these two plays exceptions. On several of the eight Moss/Owens scores Sunday, cornerbacks simply watched as these threats raced upfield, covered by no one. . . .

The soft zone works for disciplined teams such as Indianapolis, but for sketchy teams such as Washington and Buffalo, it seems to promote it's-not-my-job thinking. Hey, he wasn't my man! If the Cover 2 doesn't prevent deep strikes — and that's supposed to be the big virtue of playing Cover 2 — then what is being accomplished? Defensive coordinators, pick your best cornerback and tell him: Wherever Moss or Owens goes, you go. You're on him like glue, and it's your responsibility, no one else's. Challenge your best defender: That's the way to counter a great receiver. And before you say, "Man coverage can be burned deep," what exactly did we observe Owens and Moss doing to soft zones? Play man-to-man. It's manly!

For the benefit of readers who don't necessarily care to master the intricacies of defensive strategies in football, I've highlighted the most important portions of Easterbrook's analysis. I'll also add my own gloss on the most important defensive divide in football. Man-to-man defense operates exactly as it sounds. Each pass defender covers a specific eligible receiver. Cover 2 is a zone defense that directs speedier cornerbacks to watch shorter, snappier plays near the line of scrimmage and somewhat slower safeties (who are set back a considerable distance in the secondary) to guard deep plays. The essential difference is that man-to-man assigns individual responsibility, while Cover 2, or any other zone-based scheme, is a consciously collective effort.

For the benefit of readers who don't necessarily care to master the intricacies of defensive strategies in football, I've highlighted the most important portions of Easterbrook's analysis. I'll also add my own gloss on the most important defensive divide in football. Man-to-man defense operates exactly as it sounds. Each pass defender covers a specific eligible receiver. Cover 2 is a zone defense that directs speedier cornerbacks to watch shorter, snappier plays near the line of scrimmage and somewhat slower safeties (who are set back a considerable distance in the secondary) to guard deep plays. The essential difference is that man-to-man assigns individual responsibility, while Cover 2, or any other zone-based scheme, is a consciously collective effort.By temperament and instinct, I prefer Cover 2. It is a goal-oriented scheme as opposed to a task-oriented scheme. Its stated objective is to prevent big, back-breaking plays by whatever means emerge, as opposed to assigning specific tasks to specific players. In military terms, the equivalent is telling the entire company, "Secure the position, whatever your tactics," as opposed to issuing specific instructions to individual soldiers.

But Gregg Easterbrook correctly observes that the Cover 2 assumes that a defensive unit has the talent and the cohesion to identify and neutralize deep threats. Otherwise, a soft zone defense is just that, soft. In the face of blazing speed and preternatural instincts — of the sort typified by Randy Moss and Terrell Owens — a defense may be well advised to deviate from a pure Cover 2 scheme and restore at least one individual assignment. Randy Moss is your responsibility; don't get beat. In other words, when the going gets tough, the tough go man-to-man.

So it is with academic administration. As I've written before in this forum, the vast majority of law schools, perhaps as much as 90 percent of the industry, have missions that are distinctly less lofty than those of truly "elite" schools. Relative to the wealthiest schools, we don't have the resources to overcome shirking, mistakes in judgment, or even bad luck. As much as we'd like to play Cover 2, few of us are to legal education as the Indianapolis Colts and the New England Patriots are to professional football. For the rest of us, contending for the playoffs, let alone making the postseason and going deep against the likes of Peyton Manning and Tom Brady, depends on a judicious balance of Cover 2's team-wide resilience with the individual accountability that distinguishes man-to-man defense.

History and destiny

And when you're done pondering this analysis, check out this bonus post on the "hidden costs of tenure." Wherever she is these days, Ally McBeal would certainly appreciate the point.

And when you're done pondering this analysis, check out this bonus post on the "hidden costs of tenure." Wherever she is these days, Ally McBeal would certainly appreciate the point.

Compiled by Kenneth A. Vercammen, Esq.

The New Probate Statute of NJ revised various sections of the New Jersey law on Wills and estates. law makes a number of substantial changes to the provisions governing the administration of estates and trusts in New.

Duty of Executor in Probate Estate Administration

1. Conduct a thorough search of the decedent's personal papers and effects for any evidence which might point you in the direction of a potential creditor;

2. Carefully examine the decedent's checkbook and check register for recurring payments, as these may indicate an existing debt;

3. Contact the issuer of each credit card that the decedent had in his/her possession at the time of his/ her death;

4. Contact all parties who provided medical care, treatment, or assistance to the decedent prior to his/her death;

Your attorney will not be able to file the NJ inheritance tax return until it is clear as to the amounts of the medical bills. Medical expenses can be deducted in the inheritance tax.

Under United States Supreme Court Case, Tulsa Professional Collection Services, Inc., v. Joanne Pope, Executrix of the Estate of H. Everett Pope, Jr., Deceased, the Personal Representative in every estate is personally responsible to provide actual notice to all known or "readily ascertainable" creditors of the decedent. This means that is your responsibility to diligently search for any "readily ascertainable" creditors.

Other duties/ Executor to Do

Bring Will to Surrogate

Apply to Federal Tax ID #

Set up Estate Account at bank (pay all bills from estate account)

Pay Bills

Notice of Probate to Beneficiaries (Attorney can handle)

If charity, notice to Atty General (Attorney can handle)

File notice of Probate with Surrogate (Attorney can handle)

File first Federal and State Income Tax Return [CPA- ex Marc Kane]

Prepare Inheritance Tax Return and obtain Tax Waivers (Attorney can handle)

File waivers within 8 months upon receipt (Attorney can handle)

Prepare Informal Accounting

Prepare Release and Refunding Bond (Attorney can handle)

Obtain Child Support Judgment clearance (Attorney will handle)

Let's review the major duties involved-

In General. The executor's job is to (1) administer the estate--i.e., collect and manage assets, file tax returns and pay taxes and debts--and (2) distribute any assets or make any distributions of bequests, whether personal or charitable in nature, as the deceased directed (under the provisions of the Will). Let's take a look at some of the specific steps involved and what these responsibilities can mean. Chronological order of the various duties may vary.

Probate. The executor must "probate" the Will. Probate is a process by which a Will is admitted. This means that the Will is given legal effect by the court. The court's decision that the Will was validly executed under state law gives the executor the power to perform his or her duties under the provisions of the Will.

An employer identification number ("EIN") should be obtained for the estate; this number must be included on all returns and other tax documents having to do with the estate. The executor should also file a written notice with the IRS that he/she is serving as the fiduciary of the estate. This gives the executor the authority to deal with the IRS on the estate's behalf.

Pay the Debts. The claims of the estate's creditors must be paid. Sometimes a claim must be litigated to determine if it is valid. Any estate administration expenses, such as attorneys', accountants' and appraisers' fees, must also be paid.

Manage the Estate. The executor takes legal title to the assets in the probate estate. The probate court will sometimes require a public accounting of the estate assets. The assets of the estate must be found and may have to be collected. As part of the asset management function, the executor may have to liquidate or run a business or manage a securities portfolio. To sell marketable securities or real estate, the executor will have to obtain stock power, tax waivers, file affidavits, and so on.

Take Care of Tax Matters. The executor is legally responsible for filing necessary income and estate-tax returns (federal and state) and for paying all death taxes (i.e., estate and inheritance). The executor can, in some cases be held personally liable for unpaid taxes of the estate. Tax returns that will need to be filed can include the estate's income tax return (both federal and state), the federal estate-tax return, the state death tax return (estate and/or inheritance), and the deceased's final income tax return (federal and state). Taxes usually must be paid before other debts. In many instances, federal estate-tax returns are not needed as the size of the estate will be under the amount for which a federal estate-tax return is required.

Often it is necessary to hire an appraiser to value certain assets of the estate, such as a business, pension, or real estate, since estate taxes are based on the "fair market" value of the assets. After the filing of the returns and payment of taxes, the Internal Revenue Service will generally send some type of estate closing letter accepting the return. Occasionally, the return will be audited.

Distribute the Assets. After all debts and expenses have been paid, the executor will distribute the assets. Frequently, beneficiaries can receive partial distributions of their inheritance without having to wait for the closing of the estate.

Under increasingly complex laws and rulings, particularly with respect to taxes, in larger estates an executor can be in charge for two or three years before the estate administration is completed. If the job is to be done without unnecessary cost and without causing undue hardship and delay for the beneficiaries of the estate, the executor should have an understanding of the many problems involved and an organization created for settling estates. In short, an executor should have experience

At some point in time, you may be asked to serve as the executor of the estate of a relative or friend, or you may ask someone to serve as your executor. An executor's job comes with many legal obligations. Under certain circumstances, an executor can even be held personally liable for unpaid estate taxes. Let's review the major duties involved, which we've set out below.

In General. The executor's job is to (1) administer the estate--i.e., collect and manage assets, file tax returns and pay taxes and debts--and (2) distribute any assets or make any distributions of bequests, whether personal or charitable in nature, as the deceased directed (under the provisions of the Will). Let's take a look at some of the specific steps involved and what these responsibilities can mean. Chronological order of the various duties may vary.

Probate. The executor must "probate" the Will. Probate is a process by which a Will is admitted. This means that the Will is given legal effect by the court. The court's decision that the Will was validly executed under state law gives the executor the power to perform his or her duties under the provisions of the Will.

An employer identification number ("EIN") should be obtained for the estate; this number must be included on all returns and other tax documents having to do with the estate. The executor should also file a written notice with the IRS that he/she is serving as the fiduciary of the estate. This gives the executor the authority to deal with the IRS on the estate's behalf.

Pay the Debts. The claims of the estate's creditors must be paid. Sometimes a claim must be litigated to determine if it is valid. Any estate administration expenses, such as attorneys', accountants' and appraisers' fees, must also be paid.

Manage the Estate. The executor takes legal title to the assets in the probate estate. The probate court will sometimes require a public accounting of the estate's assets. The assets of the estate must be found and may have to be collected. As part of the asset management function, the executor may have to liquidate or run a business or manage a securities portfolio. To sell marketable securities or real estate, the executor will have to obtain stock power, tax waivers, file affidavits, and so on.

Take Care of Tax Matters. The executor is legally responsible for filing necessary income and estate-tax returns (federal and state) and for paying all death taxes (i.e., estate and inheritance). The executor can, in some cases be held personally liable for unpaid taxes of the estate. Tax returns that will need to be filed can include the estate's income tax return (both federal and state), the federal estate-tax return, the state death tax return (estate and/or inheritance), and the deceased's final income tax return (federal and state). Taxes usually must be paid before other debts. In many instances, federal estate-tax returns are not needed as the size of the estate will be under the amount for which a federal estate-tax return is required.

Often it is necessary to hire an appraiser to value certain assets of the estate, such as a business, pension, or real estate, since estate taxes are based on the "fair market" value of the assets. After the filing of the returns and payment of taxes, the Internal Revenue Service will generally send some type of estate closing letter accepting the return. Occasionally, the return will be audited.

Distribute the Assets. After all debts and expenses have been paid, the distribute the assets with extra attention and meticulous bookkeeping by the executor. Frequently, beneficiaries can receive partial distributions of their inheritance without having to wait for the closing of the estate.

Under increasingly complex laws and rulings, particularly with respect to taxes, in larger estates an executor can be in charge for two or three years before the estate administration is completed. If the job is to be done without unnecessary cost and without causing undue hardship and delay for the beneficiaries of the estate, the executor should have an understanding of the many problems involved and an organization created for settling estates. In short, an executor should have experience.

Kenneth A. Vercammen is a Middlesex County, NJ trial attorney who has published 125 articles in national and New Jersey publications on Probate and litigation topics. He often lectures to trial lawyers of the American Bar Association, New Jersey State Bar Association and Middlesex County Bar Association. He is Chair of the American Bar Association Estate Planning & Probate Committee. He is also Editor of the ABA Elder Law Committee Newsletter

He is a highly regarded lecturer on litigation issues for the American Bar Association, ICLE, New Jersey State Bar Association and Middlesex County Bar Association. His articles have been published by New Jersey Law Journal, ABA Law Practice Management Magazine, and New Jersey Lawyer. He is the Editor in Chief of the New Jersey Municipal Court Law Review. Mr. Vercammen is a recipient of the NJSBA- YLD Service to the Bar Award.

In his private practice, he has devoted a substantial portion of his professional time to the preparation and trial of litigated matters. He has appeared in Courts throughout New Jersey several times each week on many personal injury matters, Municipal Court trials, and contested Probate hearings.

KENNETH VERCAMMEN

Attorney at Law

Legal Resume

2053 Woodbridge Ave.

Edison, NJ 08817

732-572-0500

www.centraljerseyelderlaw.com

Massachusetts Youthful Offender Law Challenged in Worcester

As mentioned in my recent post Deadly Delinquents, Deadbeat Dads, and the Dangers of Demonization, there is also international human rights law support available to challenge such laws. Unfortunately, state and federal courts all the way up to the US Supreme Court often do not show the appropriate respect for, or even attention to, international law. But I say pile it on. This looks to be an interesting challenge to a bad law, one that in my opinion is violative of human rights law and of US and state constitutional law.

"WORCESTER— Lawyers for a Milford teenager charged in a fatal stabbing are challenging the constitutionality of a state law requiring that juvenile murder suspects between the ages of 14 and 17 be tried as adults. Lawyers John G. Swomley and Kenneth J. King, who represent Patrick I. Powell, contend in a motion to dismiss the murder charge pending against Mr. Powell in Worcester Superior Court that subjecting their client to a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment if he is convicted would expose him to cruel and unusual punishment under the state and federal constitutions and deny him due process. Mr. Powell was 16 when he was charged with murder in the Jan. 6, 2006, stabbing death of 21-year-old Daniel Columbo during an altercation outside Mr. Columbo’s home at 26 Carroll St. in Milford. Mr. Columbo died as a result of a stab wound to the chest allegedly inflicted by Mr. Powell.....

....

Mr. Swomley, who was appointed to represent Mr. Powell, now 18, and Mr. King, who is affiliated with the Suffolk University Law School’s Juvenile Justice Center, argue in their motion to dismiss that a juvenile offender is less culpable than an adult who engages in similar misconduct because of 'psychological and cognitive immaturity.'

'Recent advances in neuroscience explain that a juvenile’s lack of impulse control, inability to consider consequences of actions or foresee alternative courses of action and propensity to take risks that an adult would not take are products of the juvenile’s incomplete cognitive development,' according to their motion. Mr. Swomley and Mr. King are seeking to introduce expert testimony at a Jan. 16 hearing on their motion, contending 'that when a juvenile’s incomplete development is understood, it becomes apparent that juveniles are sufficiently different from adults that they cannot constitutionally be subjected to the same mandatory penalties as adults. That is, a life without parole sentence implies a determination that a juvenile offender is as culpable as an adult who commits similar acts and is irredeemable. Evidence from neuroscience demonstrates that neither premise can withstand scrutiny,' the lawyers wrote."

Legal Briefs of Supreme Judicial Court Cases Now Available on the Internet

Massachusetts Bar Association : Legal briefs of SJC cases available on court Web site: "Legal briefs of SJC cases available on court Web site As part of a continuing effort to make the court system more easily accessible to the public, the Supreme Judicial Court is now providing legal briefs filed with the full Court available on the Internet at www.ma-appellatecourts.org or at www.mass.gov/sjc. Lawyers, law students, or individuals who have an interest in particular cases can readily obtain the attorneys’ legal briefs, which are filed in the Supreme Judicial Court’s Clerk’s Office for the Commonwealth. Previously, these materials could only be obtained in hard copies by individuals requesting them in person in the Clerk’s Office. The briefs are scanned and posted with the case docket on the Court’s website about a month in advance of the Court’s scheduled sitting. The Supreme Judicial Court Clerk’s Office for the Commonwealth maintains the court records, docket, and court calendar for the cases heard by the seven Justices of the Court. Approximately 200 cases are decided by the full Court each year from September through May. In addition, single justices hear cases throughout the year. "

Lost Causes

I quote again from Wikipedia in summarizing the tenets of the Lost Cause:The Lost Cause is the name commonly given to a literary movement that sought to reconcile the traditional society of the Southern United States to the defeat of the Confederate States of America in the Civil War of 1861–1865. Those who contributed to the movement tended to portray the Confederacy's cause as noble and most of the Confederacy's leaders as examplars of old-fashioned chivalry, defeated by the Union armies not through superior military skill, but by overwhelming force.

- Confederate generals such as [Robert E.] Lee and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson represented the virtues of Southern nobility, as opposed to most Northern generals, who were characterized as possessing low moral standards, and who subjected the Southern civilian population to such indignities as [William Tecumseh] Sherman's March to the Sea and Philip Sheridan's burning of the Shenandoah Valley in the Valley Campaigns of 1864.

- Losses on the battlefield were inevitable due to Northern superiority in resources and manpower.

- Losses were also the result of betrayal and incompetence on the part of certain subordinates of General Lee. . . .

- Defense of states' rights, rather than preservation of chattel slavery, was the primary cause that led eleven Southern states to secede from the Union, thus precipitating the war.

- Secession was a justifiable constitutional response to Northern cultural and economic aggressions against the Southern way of life.